Structure of a Decision Analysis

Decision Trees & Probabilities

Learning Objectives and Outline

00

Learning Objectives

Construct and solve a decision problem by calculating an intervention’s expected value across competing strategies in a decision tree

Determine the decision threshold across a range of scenarios

Differentiate between joint and conditional probabilities and demonstrate their use in decision trees

Outline

01

02

Determining the Decision Threshold

03

Probabilities within Decision Trees

04

Other Concepts in Decision Analysis

05

Strengths and limitations of decision trees

06

Decision tree do’s and don’ts

The Structure of a Decision Analysis

01

Recap: Decision Analysis

Aims to inform choice under uncertainty using an explicit, quantitative approach

Aims to identify, measure, & value the consequences of decisions (risks/benefits) & uncertainty when a decision needs to be made, most appropriately over time

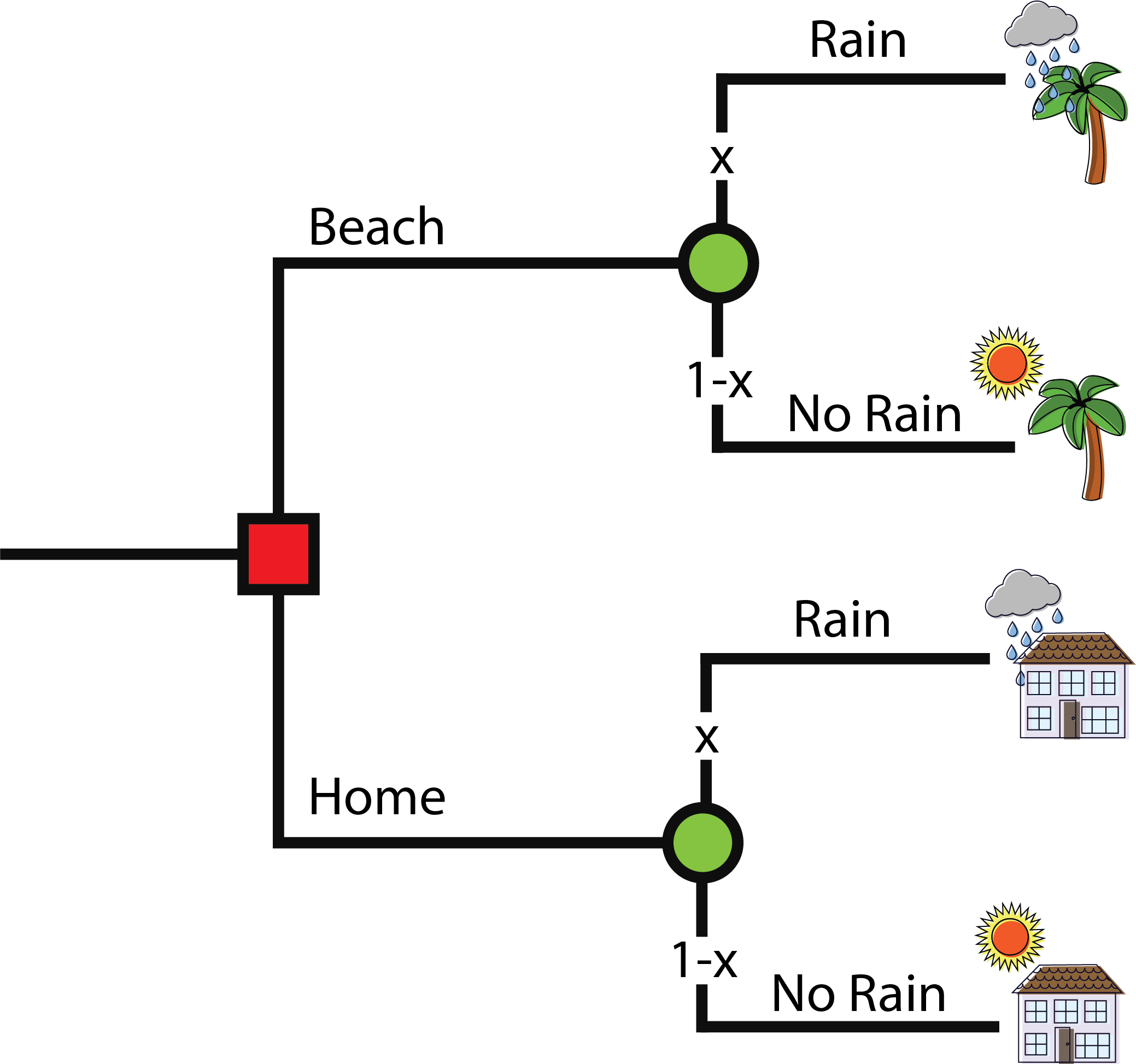

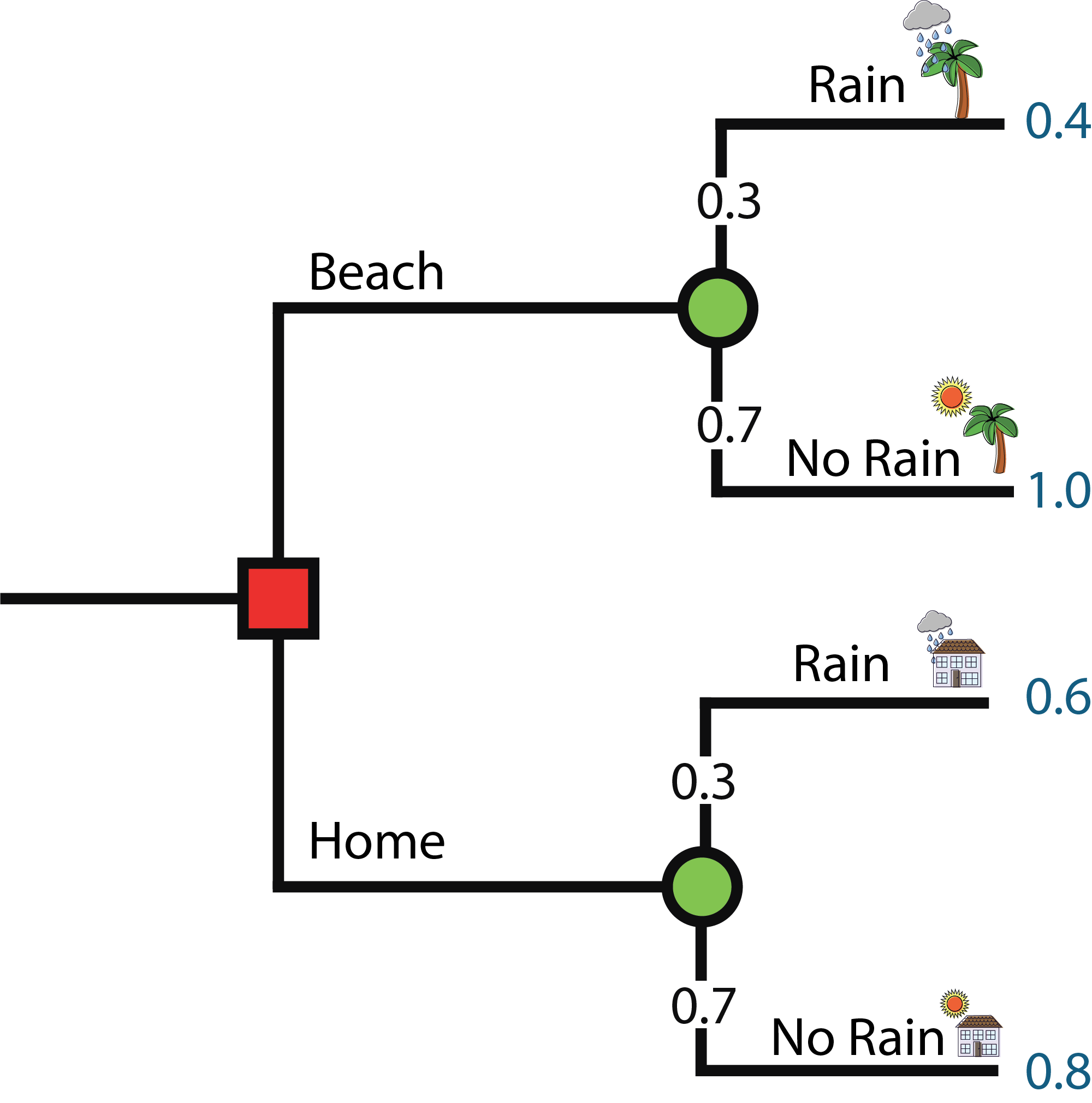

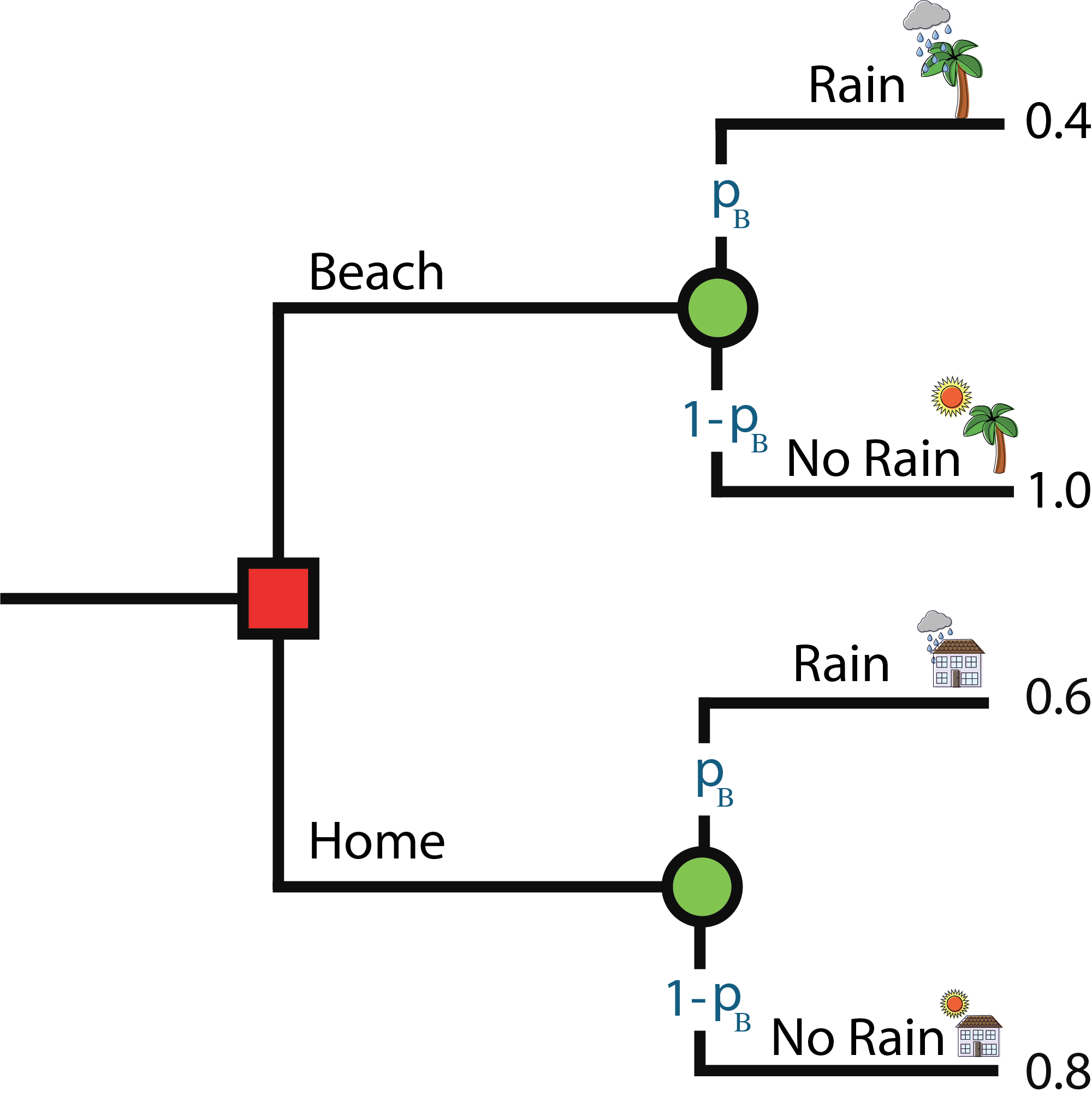

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Possible States of the World:

At the beach with no rain.

At the beach with rain.

At home with no rain.

At home with rain.

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Considerations:

Probabilities

Likelihood of Rain

Payoff

My overall well being in each state.

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Considerations:

Probabilities

Likelihood of Rain

Payoff

Mood when it is sunny at the beach

Payoff

Mood when it is raining at the beach

Payoff

Mood when it is sunny at home

Payoff

Mood when it is raining at home

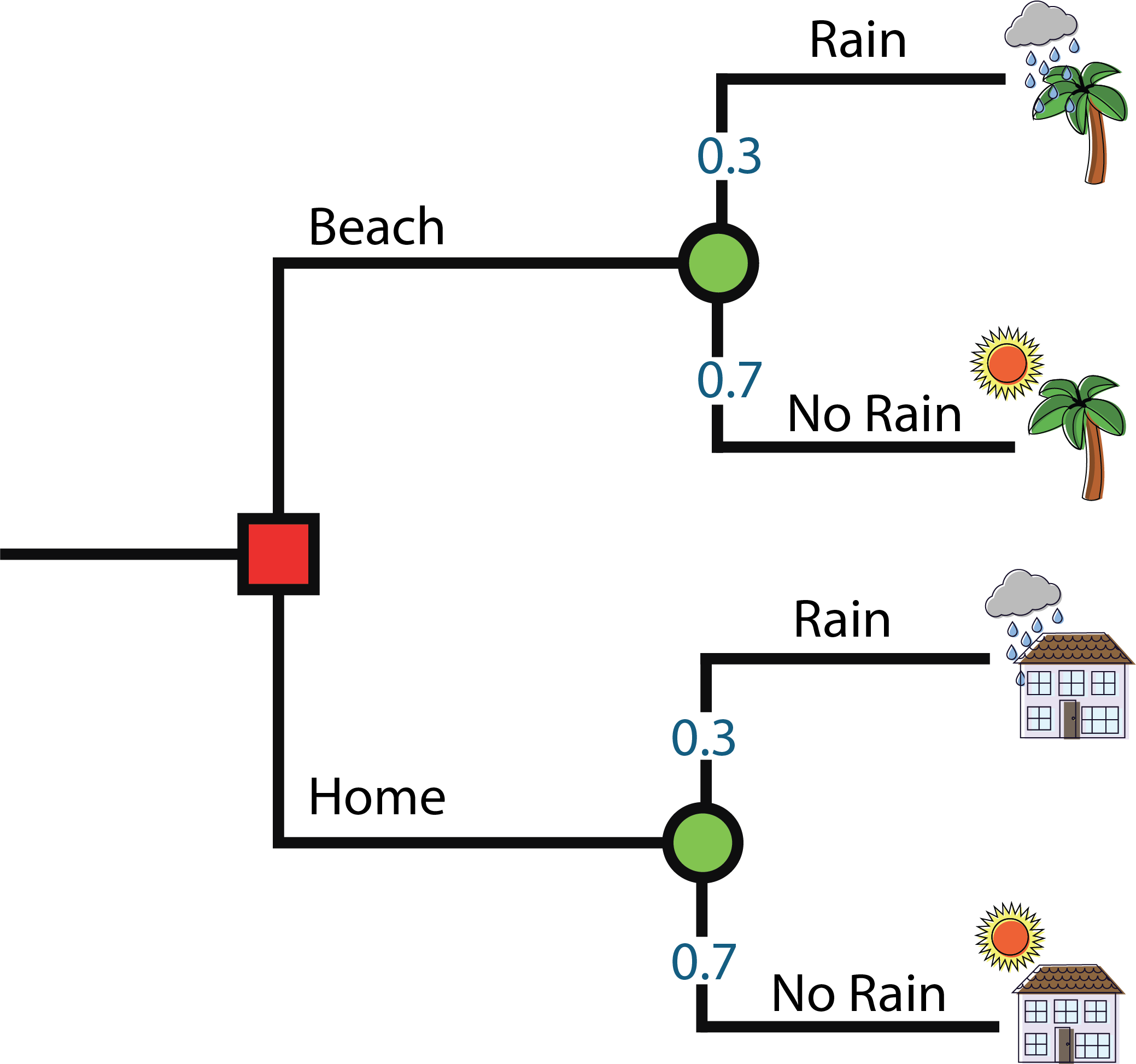

Decision Trees

Square decision node

- Indicates a decision point between alternative options

Circular Chance Node

- Shows a point where two or more alternative events for a patient are possible

Decision Trees

- Pathways are mutually exclusive sequences of events and are the routes through the tree.

- Probabilities show the likelihood of particular event occurring at a chance node.

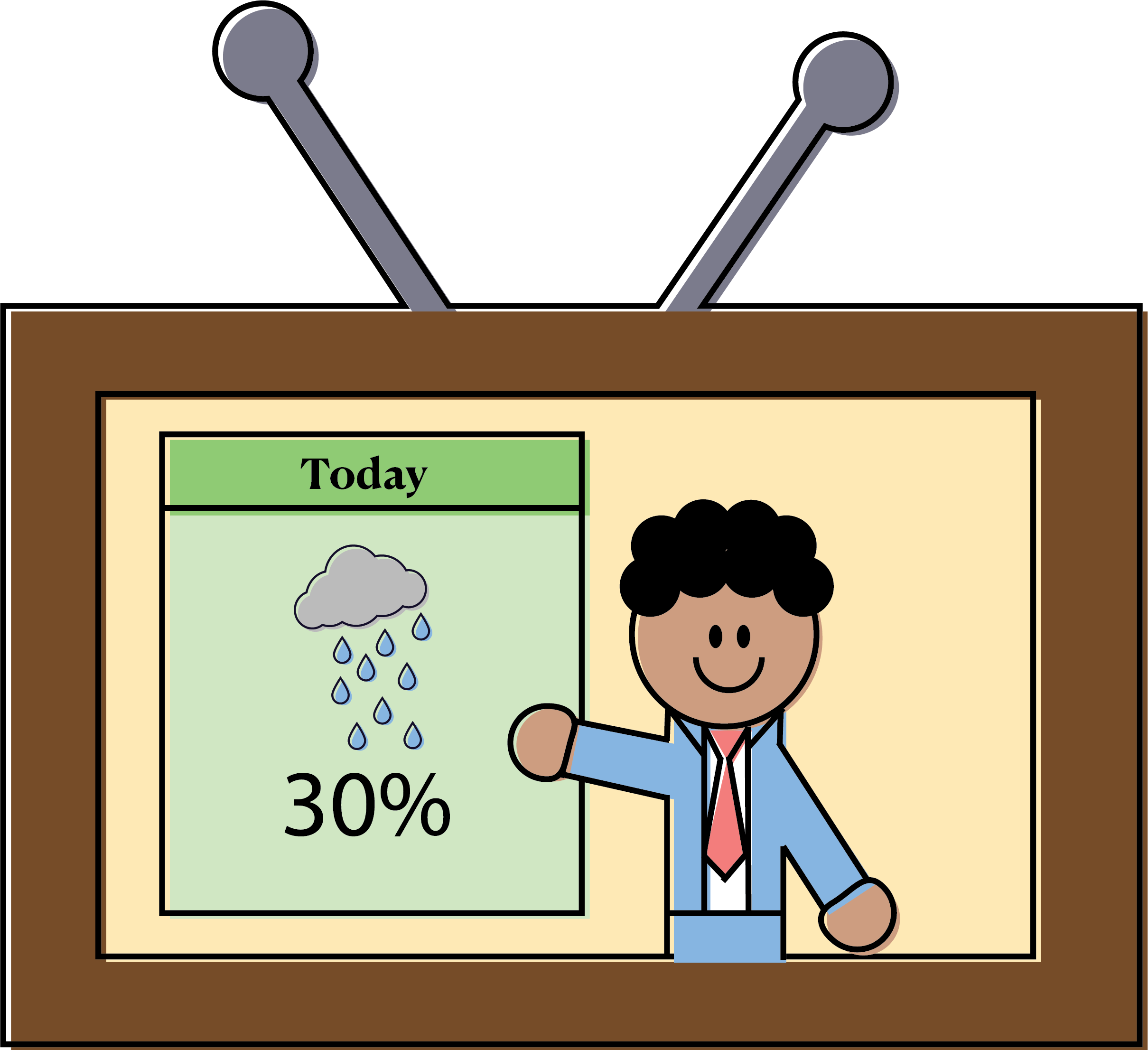

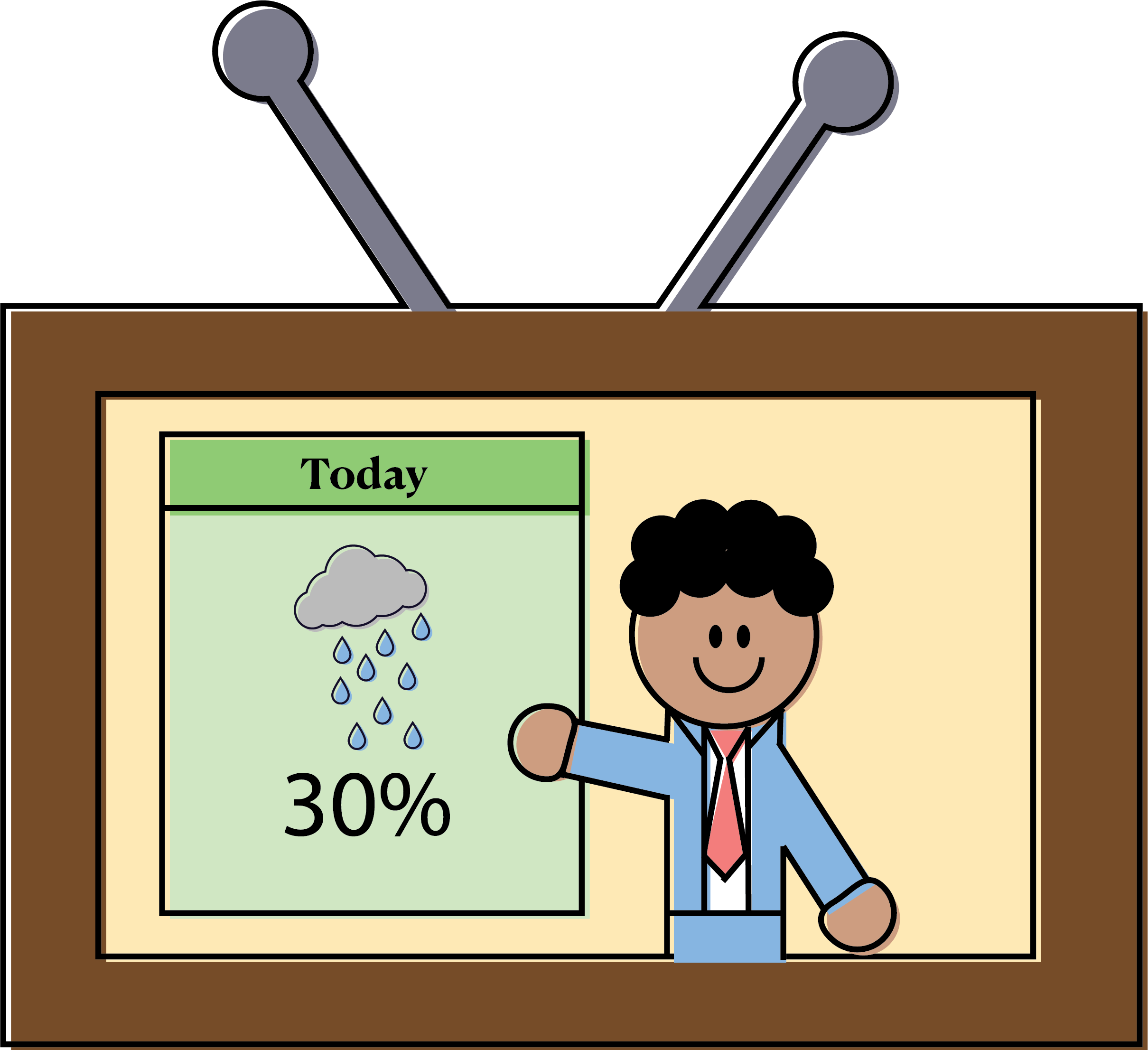

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Decision Tree:

Probability of rain = 30%

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Decision Tree:

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Payoffs

| Scenario | Payoff |

|---|---|

At beach, no rain At beach, no rain |

1.0 |

At beach, rain ↓ At beach, rain ↓ |

0.4 |

At home, no rain ↑ At home, no rain ↑ |

0.8 |

At home, rain ↑ At home, rain ↑ |

0.6 |

| Scenario | Payoff |

|---|---|

At beach, no rain BEST At beach, no rain BEST |

1.0 |

At home, no rain At home, no rain |

0.8 |

At home, rain At home, rain |

0.6 |

At beach, rain WORST At beach, rain WORST |

0.4 |

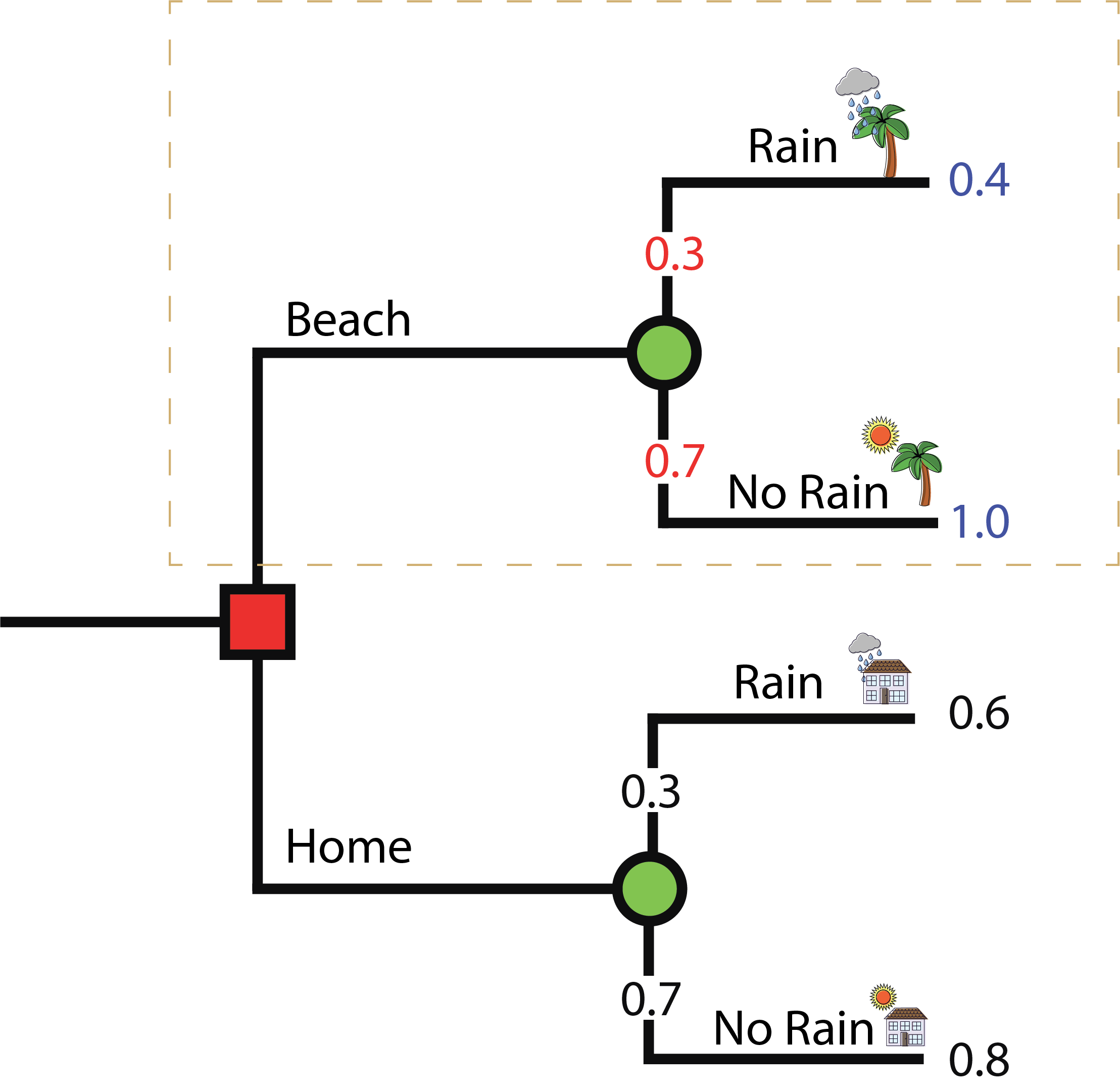

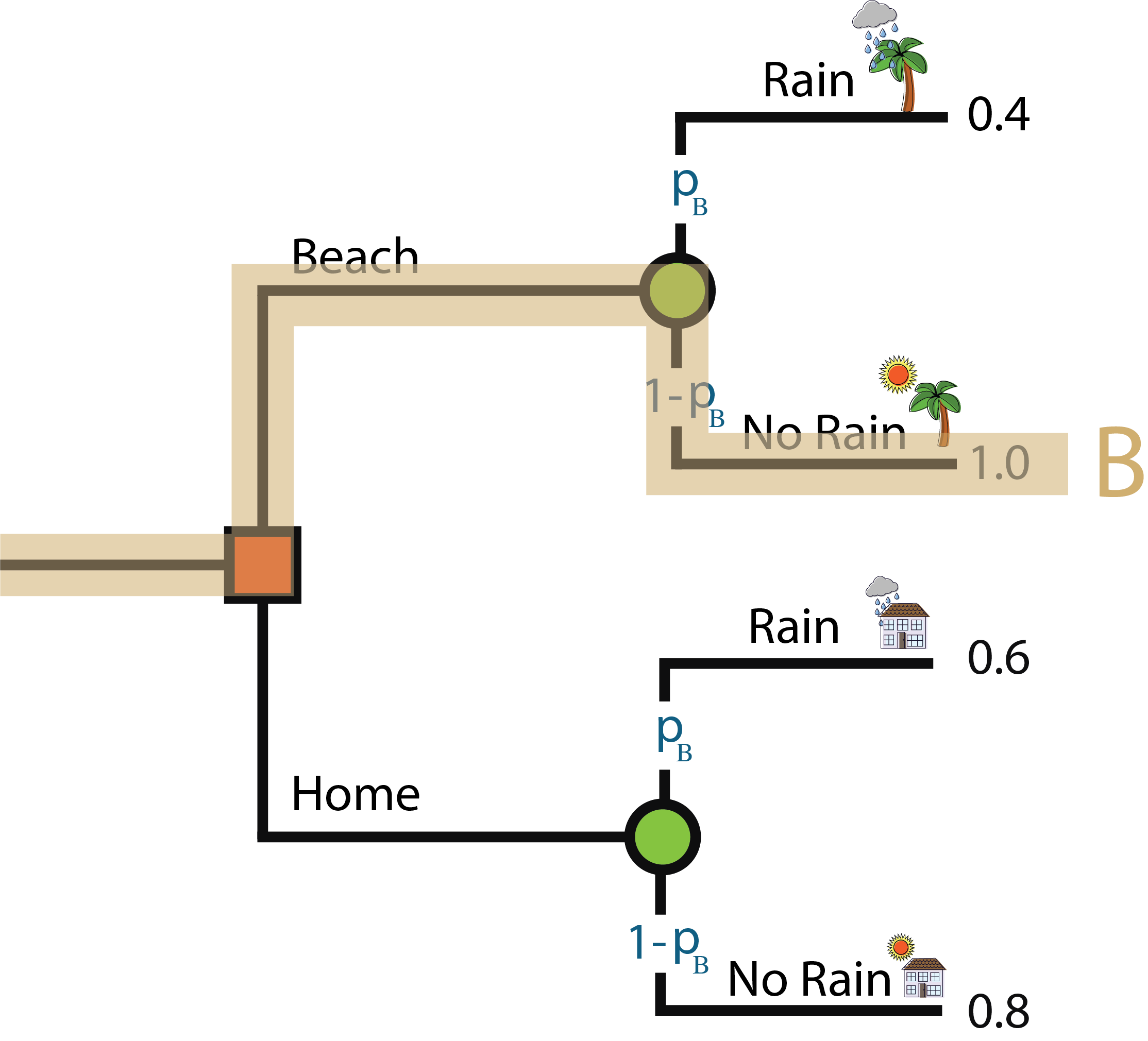

Should I go to the beach or stay home?

Decision Tree:

What is the expected value of going to the beach?

\color{green}{0.82} = \underbrace{\color{red}{0.3} * \color{blue}{0.4}}_{\text{Rain}} + \underbrace{\color{red}{0.7} * \color{blue}{1.0}}_{\text{No Rain}}

- Probabilities in red.

- Payoffs in blue.

- Expected value in green.

What is the expected value of staying home?

\color{green}{0.74} = \underbrace{\color{red}{0.3} \cdot \color{blue}{0.6}}_{\text{Rain}} + \underbrace{\color{red}{0.7} \cdot \color{blue}{0.8}}_{\text{No Rain}}

- Probabilities in red.

- Payoffs in blue.

- Expected value in green.

Beach

EV(Beach)=0.82 > EV(Home)=0.74

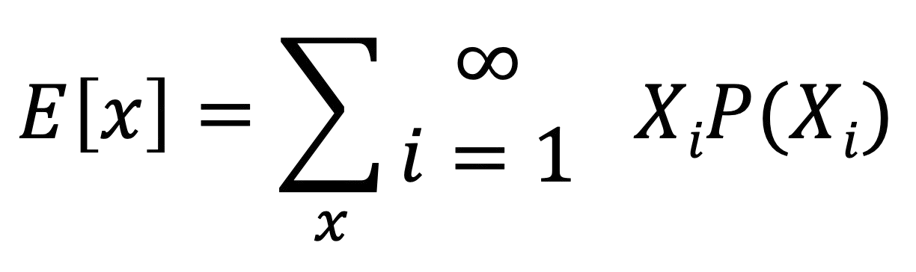

Expected Values

- Expected value = The sum of the multiplied probabilities for each chance option or intervention

Expected Values

- The expected value within the context of decision trees are the “payoffs” weighted by their preceding probabilities

- What we get is: the result that is expected ON AVERAGE for any one decision alternative (e.g. length of life, quality of life, lifetime costs)

Example:

On average, patients given Treatment A will live 0.30 years (or 3.6 months [=0.30*12]) longer than patients given Treatment B

Maximizing expected value is a reasonable criterion for choice given uncertain prospects; though it does not necessarily promise the best results for any one individual

Determining the Decision Threshold

02

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

Suppose we want to know at what probability of rain p we are indifferent between going to the beach vs. staying at home…

Write the equation for each choice using a variable, p, for the probability in question

Set the equations equal to to one other and solve for p.

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

Beach: 0.82 = 0.3 x 0.4 + 0.7 x 1.0

Home: 0.74 = 0.3 x 0.6 + 0.7 x 0.8

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

\underbrace{0.3 * 0.4 + 0.7 * 1.0}_{\text{Beach}} = \underbrace{0.3 * 0.6 + 0.7 * 0.8}_{\text{Home}}

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

Replace probability of rain with P and 1-P and solve for “P”

p * 0.4 + (1-p) * 1.0 = p * 0.6 + (1-p) * 0.8

\underbrace{0.3 * 0.4 + 0.7 * 1.0}_{\text{Beach}} = \underbrace{0.3 * 0.6 + 0.7 * 0.8}_{\text{Home}}

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

p * 0.4 + (1-p) * 1.0 = p * 0.6 + (1-p) * 0.8

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

p * 0.4 + (1-p) * 1.0 = p * 0.6 + (1-p) * 0.8

0.4p + 1-p = 0.6p + 0.8 - 0.8p

1-0.6p = 0.8 - 0.2p

1-0.8 = 0.6p - 0.2p

0.2 = 0.4 * p

0.5 = p

At what probability p are the two choices equal?

When the probability of rain is 50% at BOTH the beach and home, given how we weighted the outcomes, going to the beach would be the same as staying at home

In other words, you would be indifferent between the two – staying at home or going to the beach; <50%, you would choose the beach.

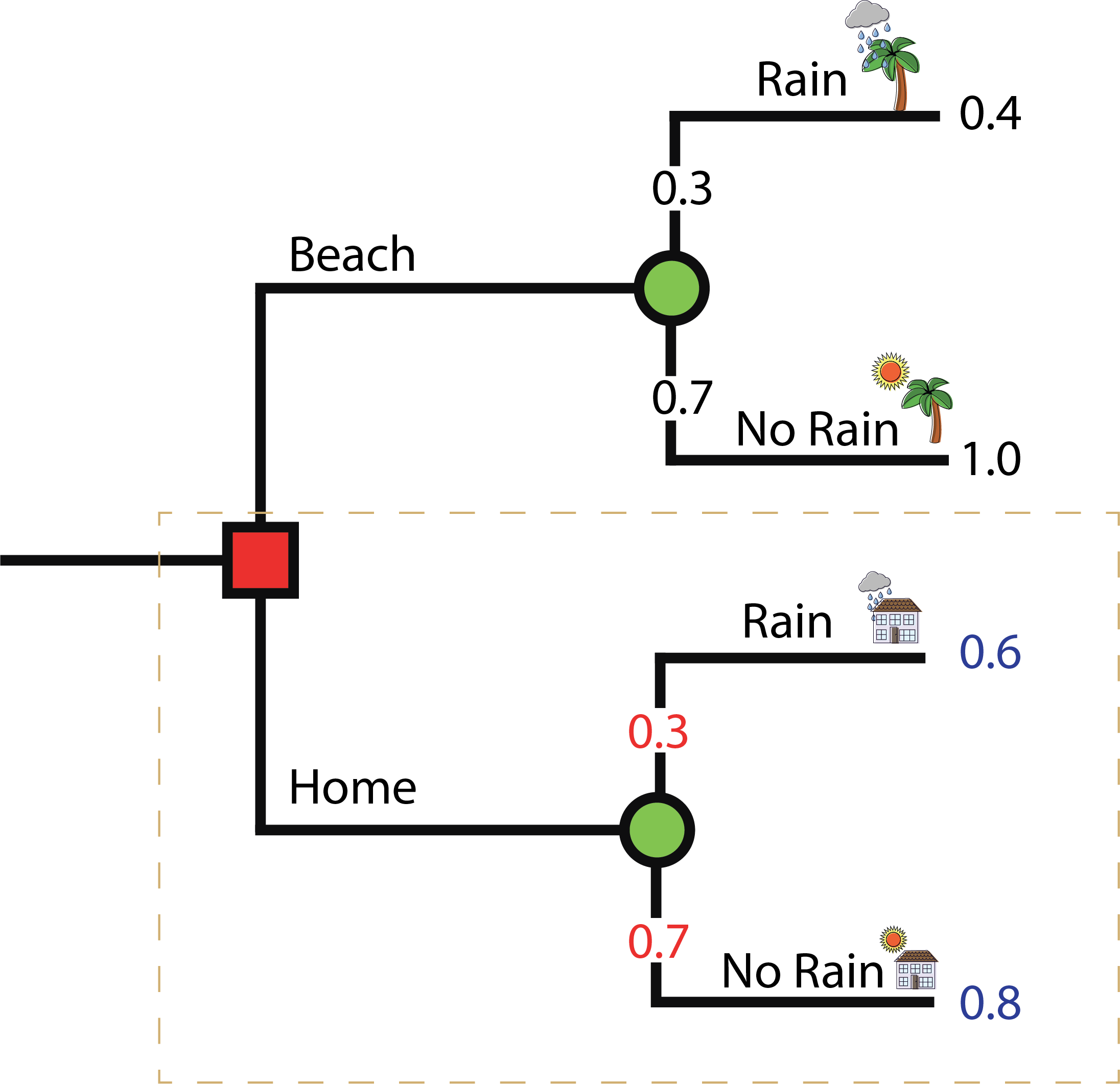

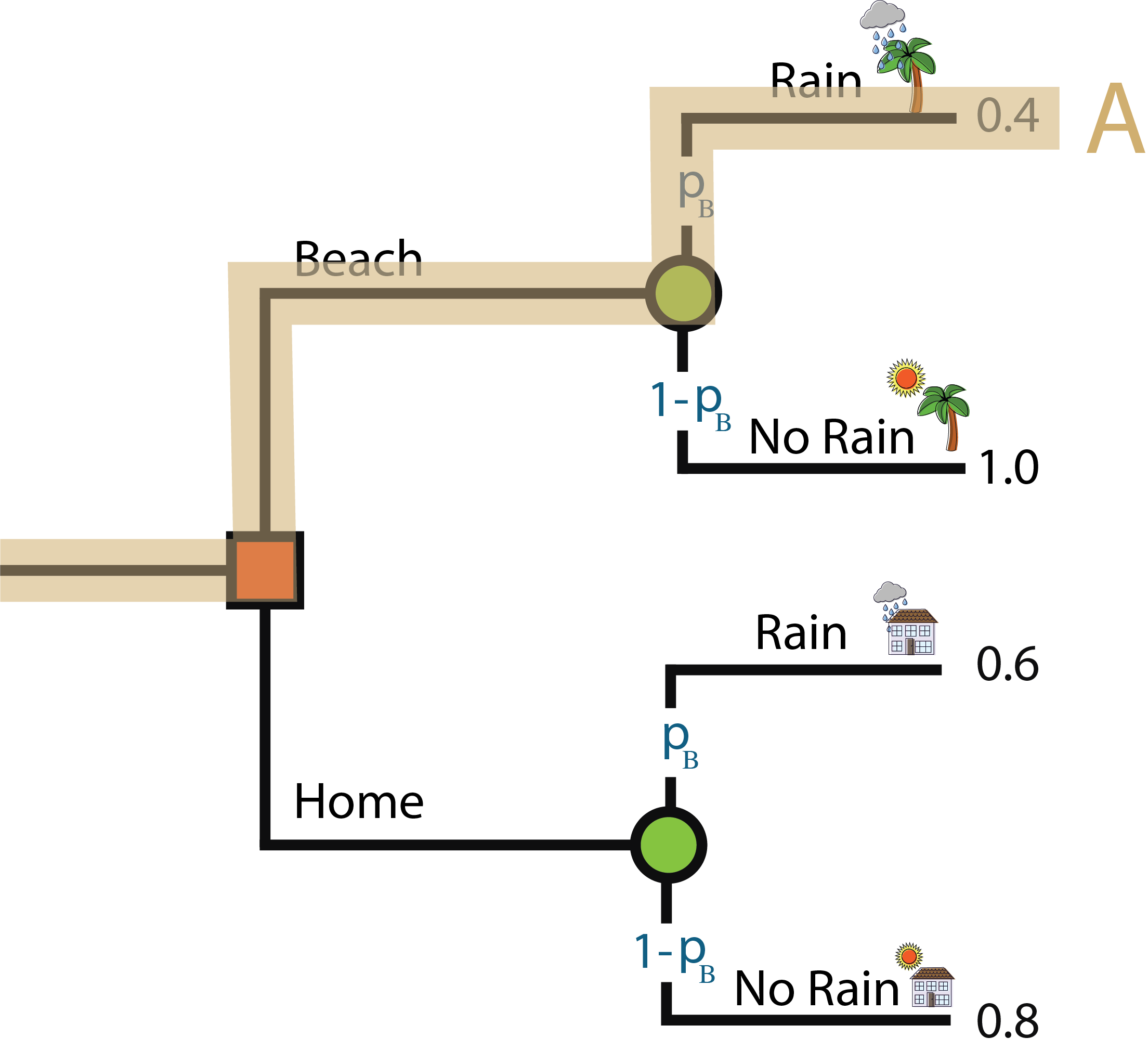

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

Earlier, we solved for the expected value of remaining at home:

0.74 (which was a lower expected value than going to the beach when the chance of rain at both was 30%)

- What would p_B need to be to yield an expected value at the beach of 0.74?

- We just solved for the indifference threshold assuming the probability of rain was the same at the beach and at home.

- Now we vary rain at the beach while keeping the probability of rain at home fixed at 30%.

- In other words, at what probability of rain at the beach would you be indifferent between staying at home & going to the beach?

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

Set 0.74 (expected value of remaining at home) equal to the beach payoffs and solve for p_B, because we are varying the probability of rain at the beach (p_B), not the probability of rain at home (p_H).

pB * 0.4 + (1 - pB) * 1.0 = 0.74

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

pB * 0.4 + (1 - pB) * 1.0 = 0.74

pB * 0.4 + 1 - pB = 0.74

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

pB * -0.6 = -0.26

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

pB = -0.26 / -0.6 = 0.43

At what probability (p_B) of rain for the beach are you indifferent between the two options?

When the probability of rain at the beach is 43% (probability of rain at home remains at 30%), we would be indifferent between staying at home & going to the beach (because the EV would both = 0.74).

If the probability of rain at the beach in >43%, then we would stay home

Remember: when the probability of rain was 30% at both locations, we would choose the beach.

Probabilities within Decision Trees

03

Mutually exclusive events

2 things that cannot occur together (one event cannot occur at the same time as the other event)

Examples:

- 2 events – survive or die

- 2 events – cured or not cured

Mutually exclusive events in Decision Trees

Mutually exclusive events

Assuming events are mutually exclusive, then the probability of 2 events occurring is the sum of the probability of each event occurring individually

P(A or B) = P(A) + P(B)

This is what we do when summing pathways for a single decision

(e.g., Beach = rain or no rain; Home = rain or no rain).

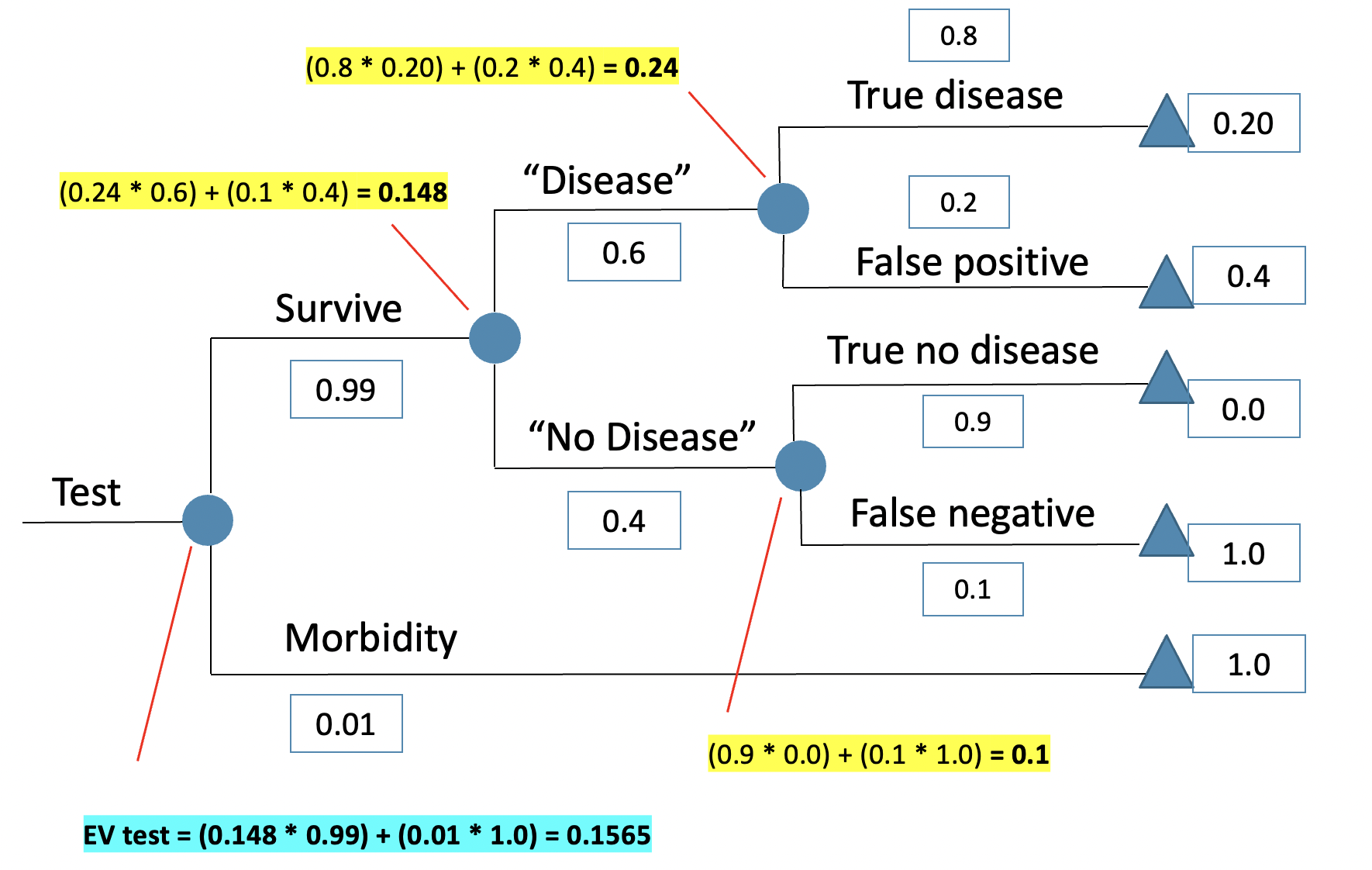

Probabilities within Decision Trees

Joint probability

P(A and B): The probability of two events occurring at the same time.

Conditional probability

P(A|B): The probability of an event A given that an event B is known to have occurred.

Probabilities

- Moving from left to right, the first probabilities in the tree show the probability of an event.

- Subsequent probabilities are conditional. The probability of an event given that an earlier event did or did not occur.

- Multiplying probabilities along pathways estimates the pathway probability, which is a joint probability.

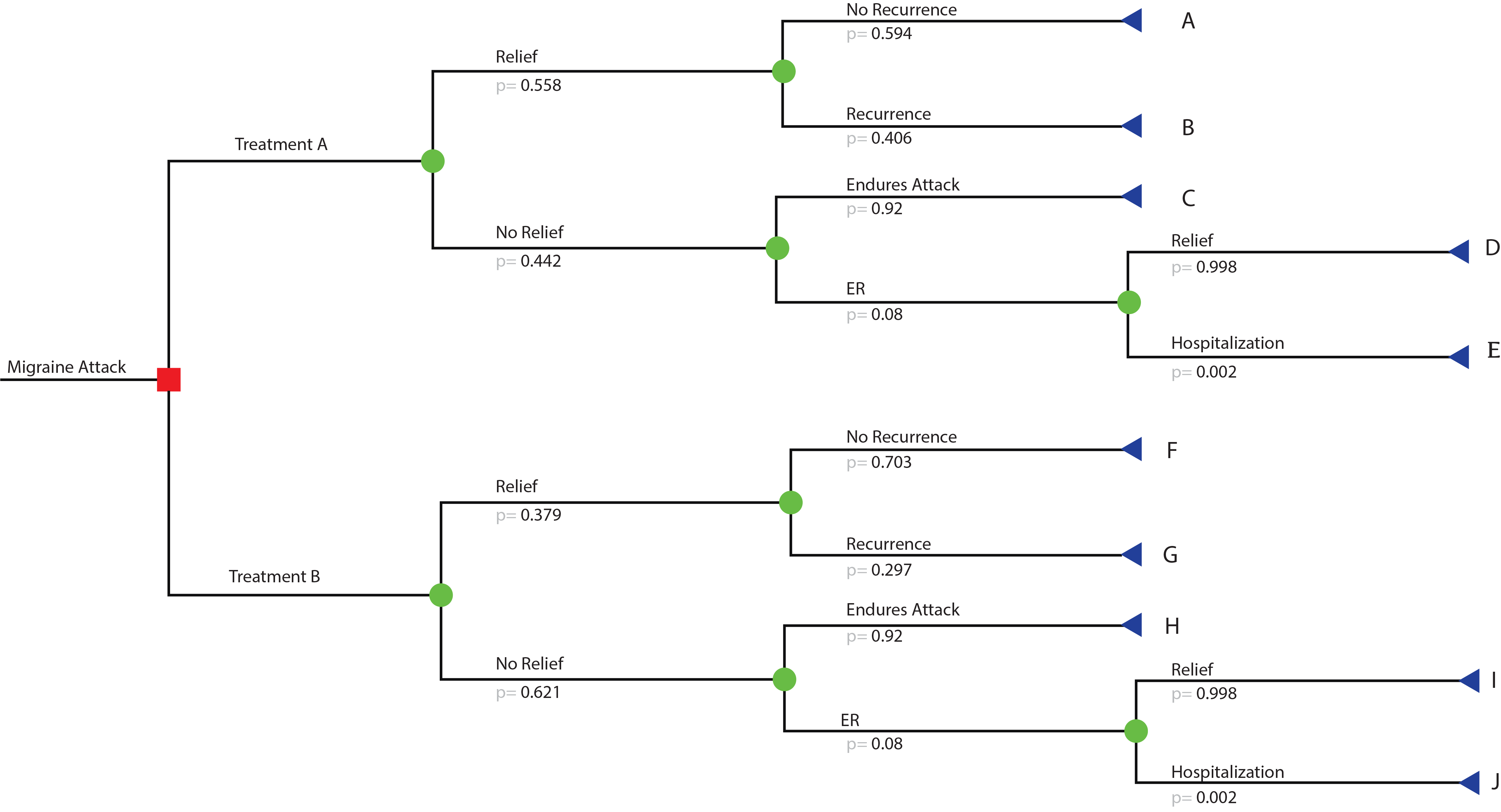

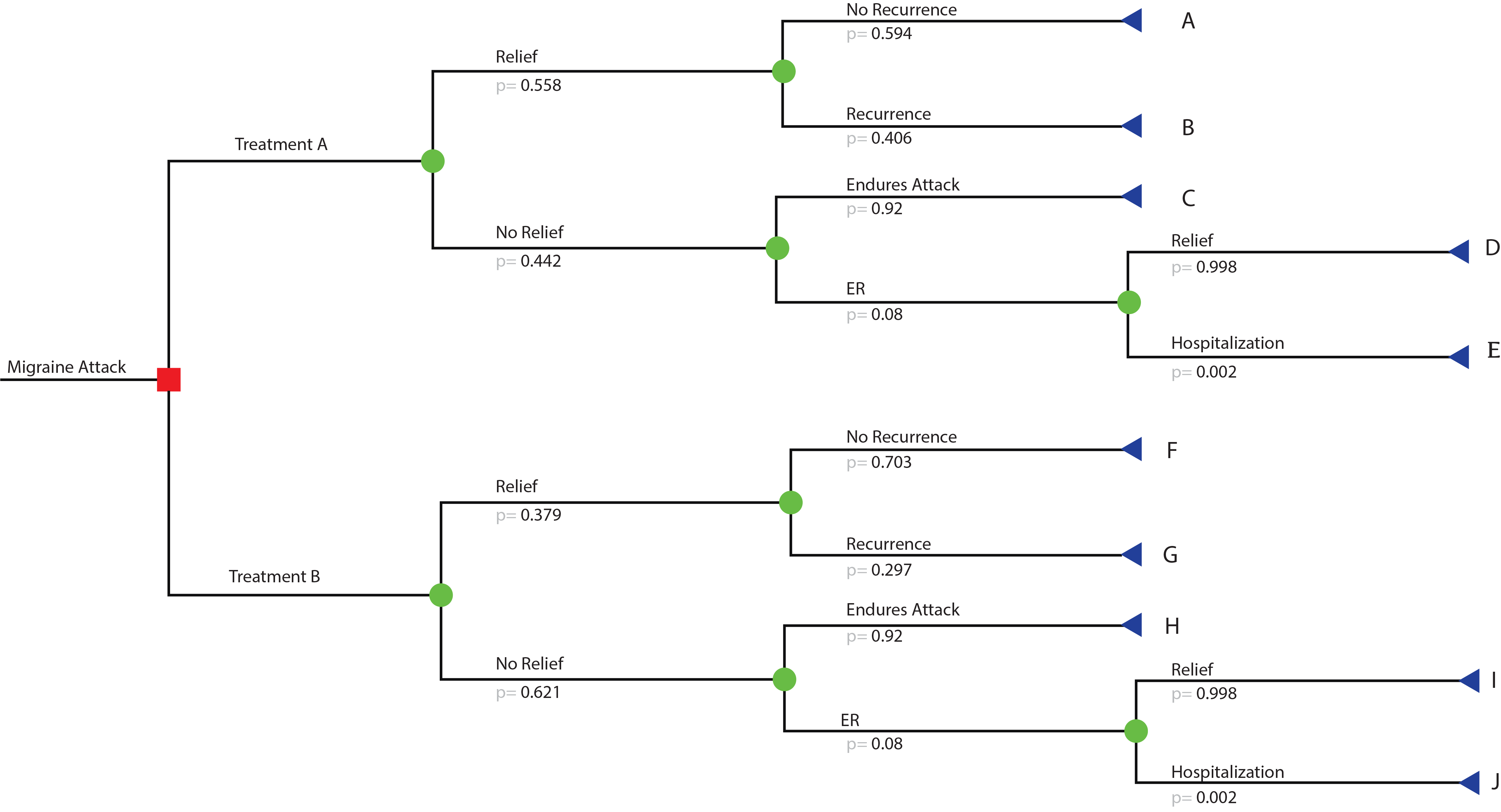

Decision Tree

Pathways

A sequence of events that lead to a subsequent “pay off” In other words, a sequence of events leads to an outcome/consequence, or payoff.

Example:

Our beach example has 4 pathways; At home with sun, at home with rain, at the beach with sun, and at the beach with rain.

Pathways

Pathway A: This person goes to the beach but it rains

Pathway B: This person goes to the beach but there is no rain

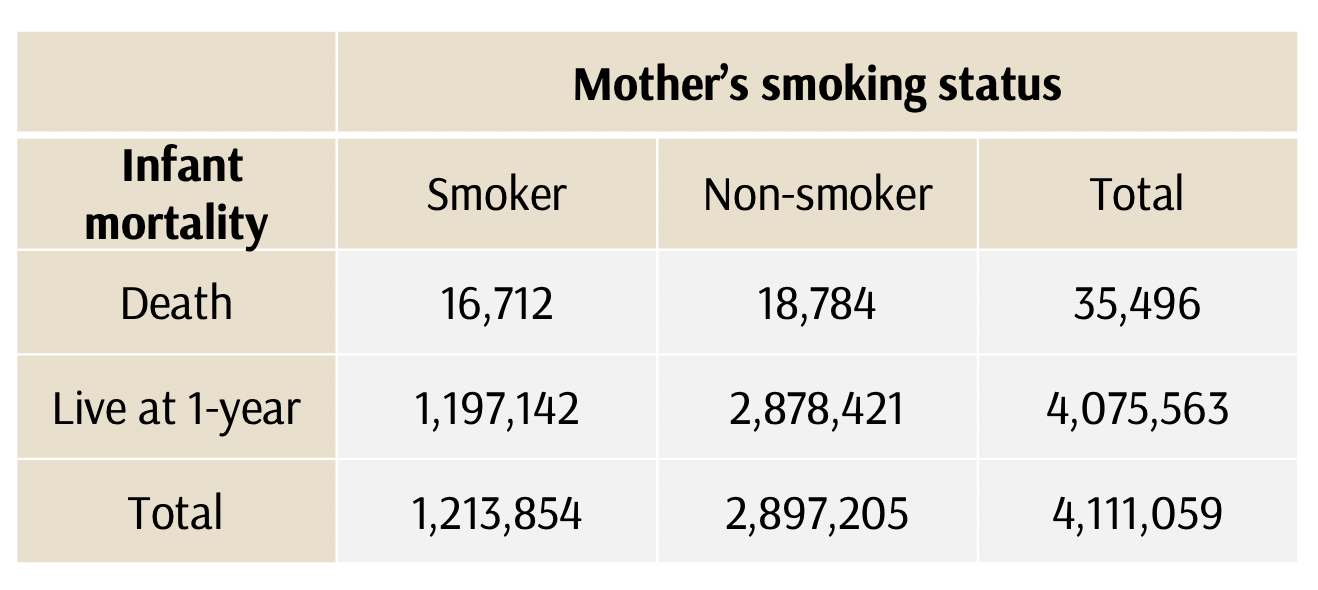

Conditional probability

Probability of an event occurring (B) given that another event occurred (A) P(A|B) = P(A and B) / P(B)

Example:

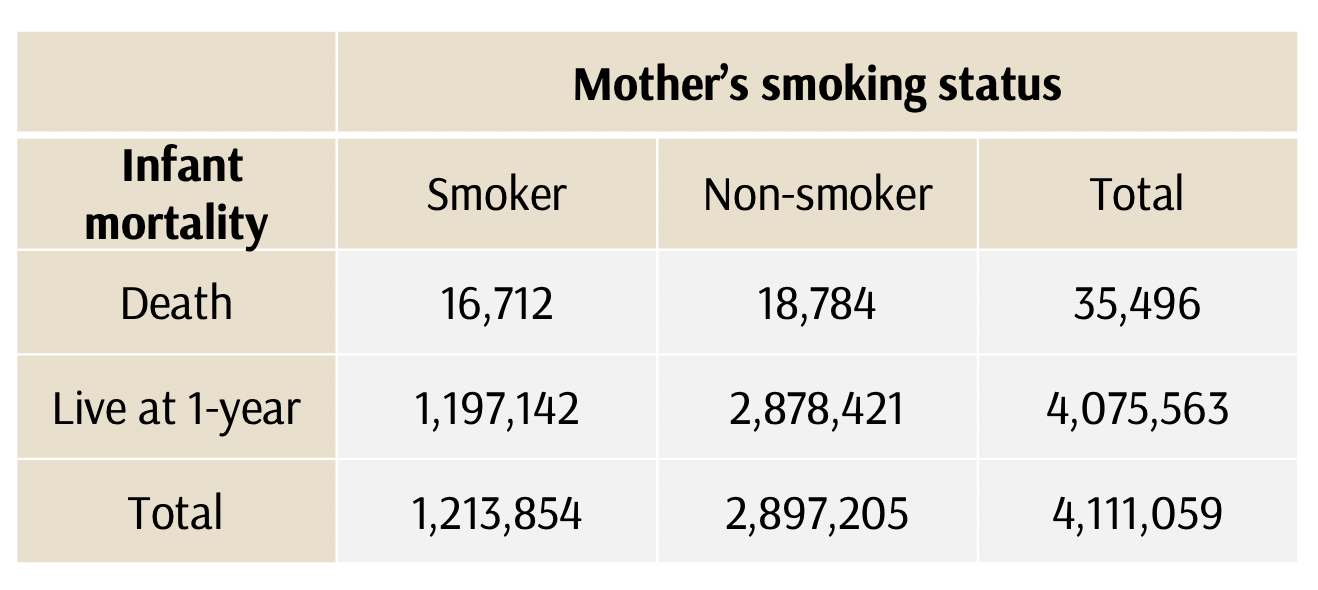

What is the conditional probability of death within a year of birth, given the infant has a mother who smokes?

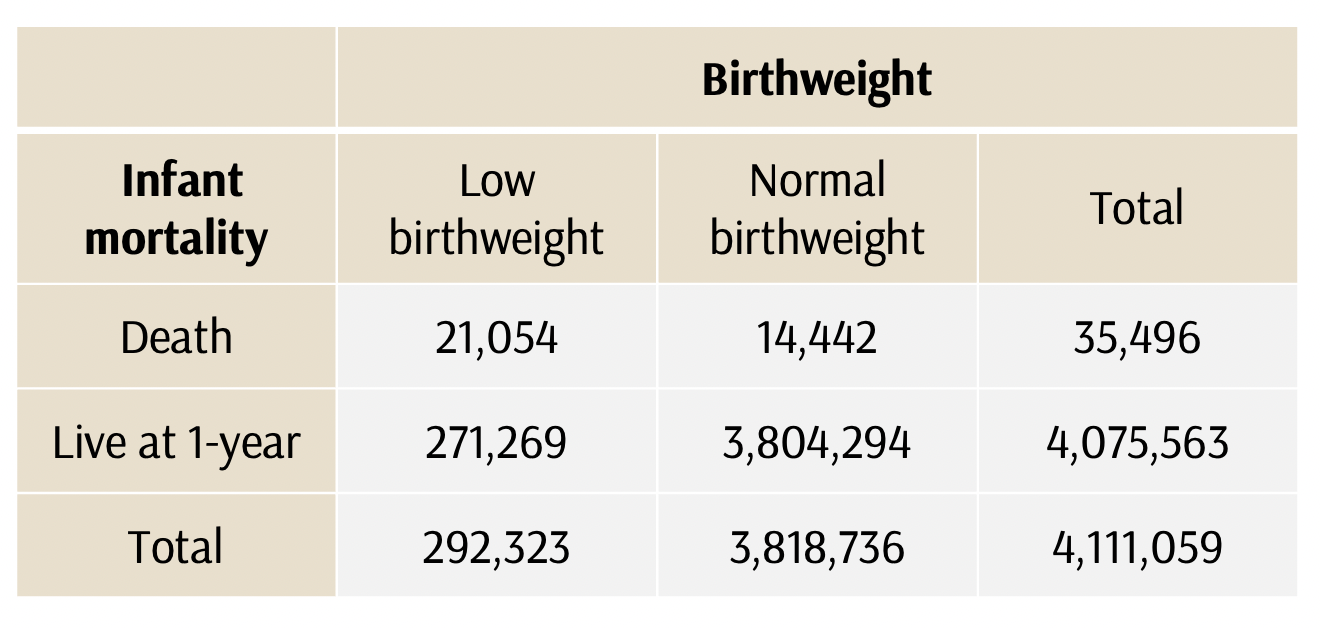

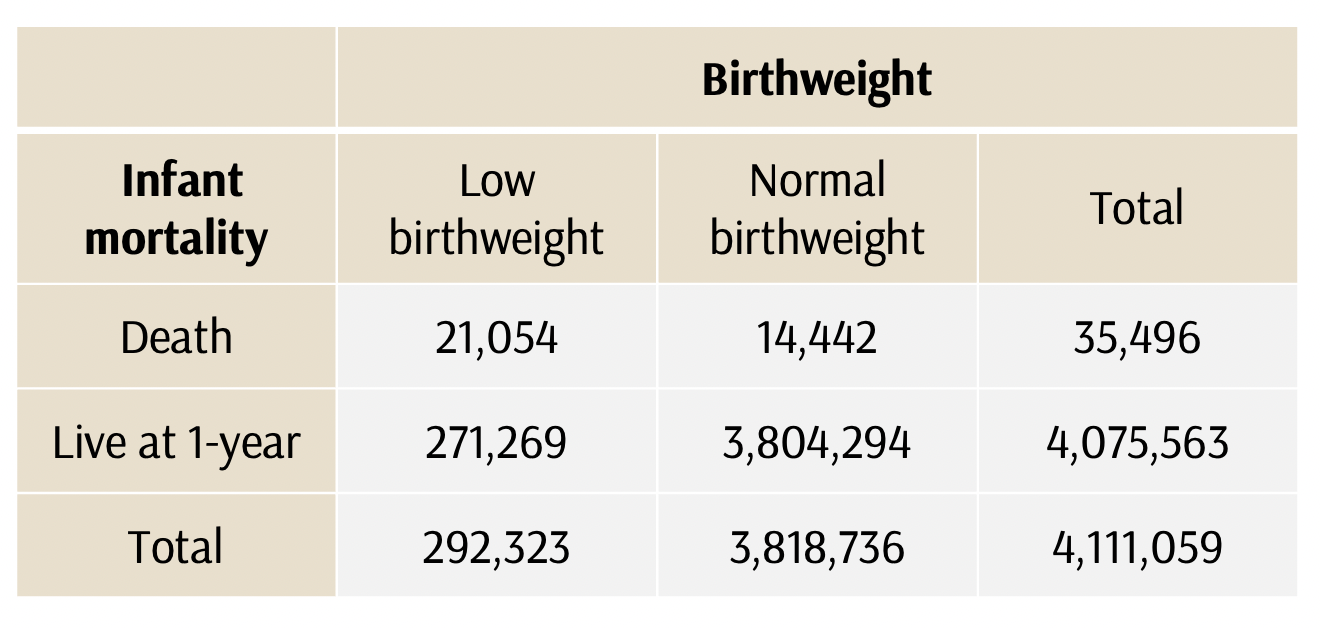

Conditional probability, 2x2 review

What is the conditional probability of death within a year of birth, given the infant has a mother who smokes?

P(A|B)

= P(death in first year | mother who smokes)

= 16,712 / (1,197,142 + 16,712)

= 14 per 1,000 births

Conditional probability, 2x2 review

Or, if we wanted to use the conditional probability equation

P(A|B) = P(A and B)/P(B)

*A= death in first year; B=mother who smokes

P(A and B) = 16,712 / 4,111,059 = 0.0041

P(B) = 1,213,854/4,111,059 = 0.295

P(A|B) = 0.0041/0.295 = 0.014

Conditional probability, A|B vs B|A

Probability of A|B is different from that of B|A

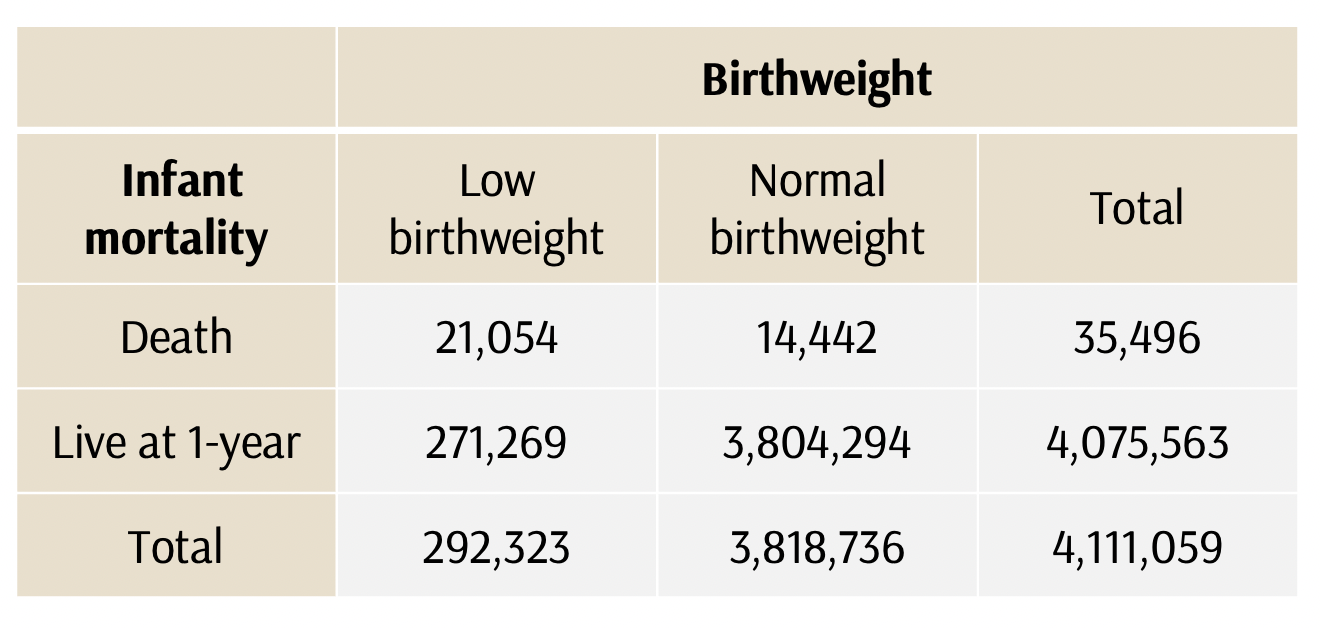

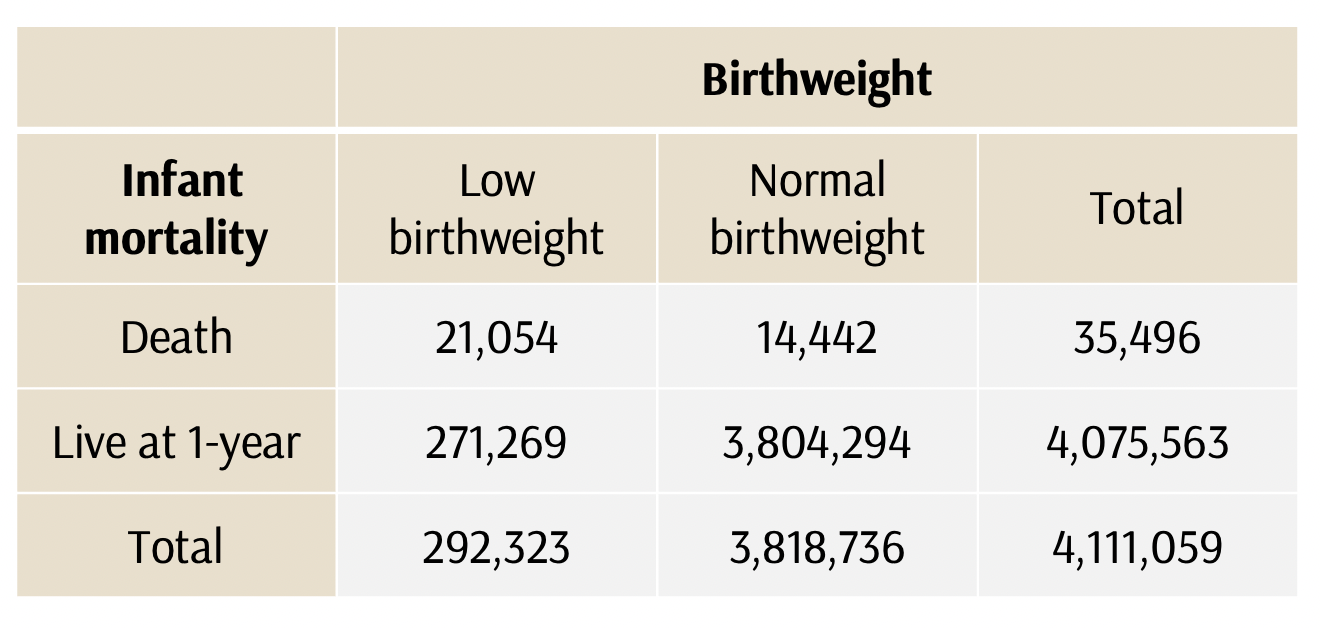

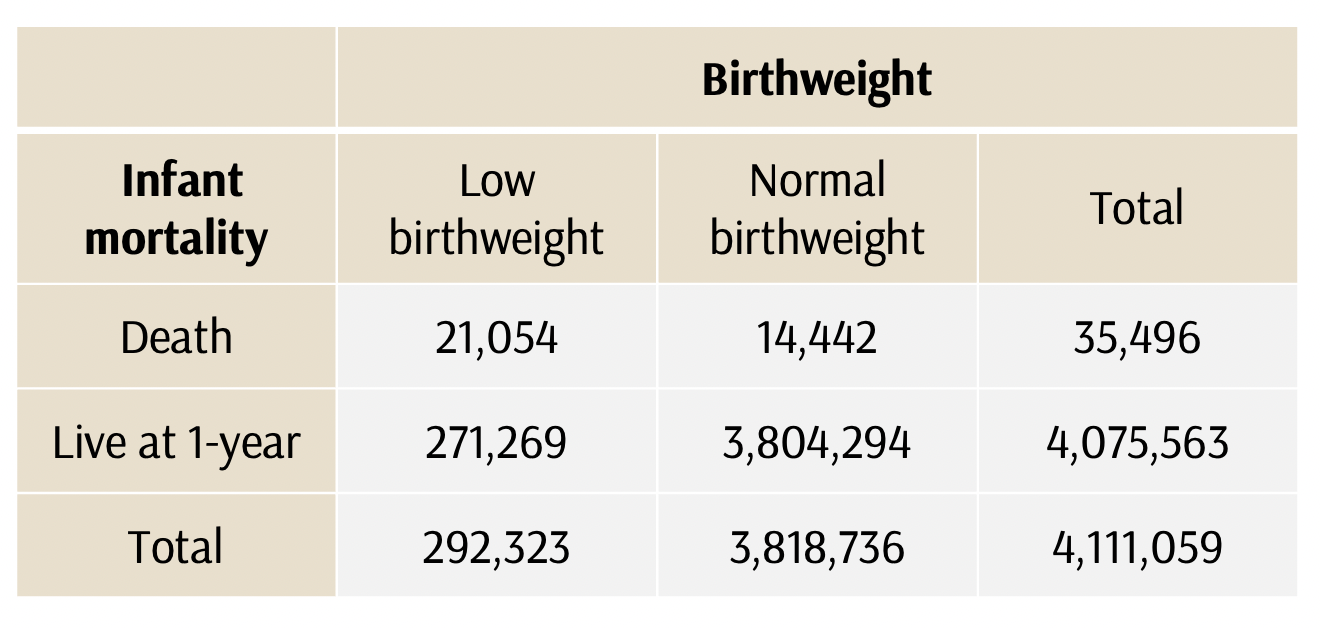

If A = death in first year; B=normal birth weight infant,

THEN, the conditional probability of P(A|B) = the probability of an infant death, given that the child has a normal birth weight

Conditional probability, A|B vs B|A

What is the conditional probability of an infant death, given that the child has a normal birth weight?

If A = death in first year; B=normal birth weight infant

P(A|B)

= 14,442 / (14,442+ 3,804,294)

= 3.8 deaths per 1,000 births

Conditional probability, A|B vs B|A

Or, if we wanted to use the conditional probability equation

P(A|B) = P(A and B)/P(B)

P(A and B) = 14,442

P(B)= 3,818,736

P(A|B) = 14,442/3,818,736 = 0.0038

* A= death in first year; B=normal birth weight infant

Conditional probability, A|B vs B|A

On the other hand, the conditional probability of P(B|A) is the probability that an infant had normal birth weight, given that the infant died within 1 year from birth

*B=normal birth weight infant; A = death in first year

Conditional probability, A|B vs B|A

Probability of A|B is 3.8 deaths per 1,000 births

Solve P(B|A) – the probability that an infant had normal birthweight, given that the infant died within 1 year from birth

P(B|A)

= 14,442 / (14,442+ 21,054)

= 0.41

4.1 normal birthweights of 1,000 baby deaths within 1 year from birth

*B=normal birth weight infant; A = death in first year

Other Concepts in Decision Analysis

04

Decision Philosophies

Maximizing expected value is a reasonable criterion for choice given uncertain prospects; though it does not necessarily promise the best results for any one individual.

Mini-max regret

- Never go to the beach unless 0% rain.

Maxi-max

- Always go to the beach unless 100% rain.

Expected utility

- Depends on the weather.

Payoffs

- Each state of the world is assigned a cost or outcome.

- Our goal is often to calculate the expected value of these payoffs.

We’ll cover more on the theories and frameworks underlying various payoffs in the next few lectures

Strengths/limitations of decision trees

05

Strengths/limitations of decision trees

Strengths

- They are easy to describe and understand

- Works well with limited time horizon

- Decision trees are a powerful framework for analyzing decisions and can provide rapid/useful insights, but they have limitations.

Limitations

- No explicit accounting for the elapse of time.

- Recurrent events must be separately built into model.

- Fine for short time cycles (e.g., 12 months) but we often want to model over a lifetime.

- Difficult to incorporate real clinical detail - Tree structure can quickly become complex.

Some Do’s & “Dont’s

06

Some Do’s & “Dont’s as you think about your own trees

- Balance risks and benefits

Each strategy must include all relevant risks and benefits.

If one option carries only risks or only benefits, either the model is misspecified or the clinical problem does not require a decision analysis (the decision would be “obvious” in the latter case).

Some Do’s & “Dont’s”

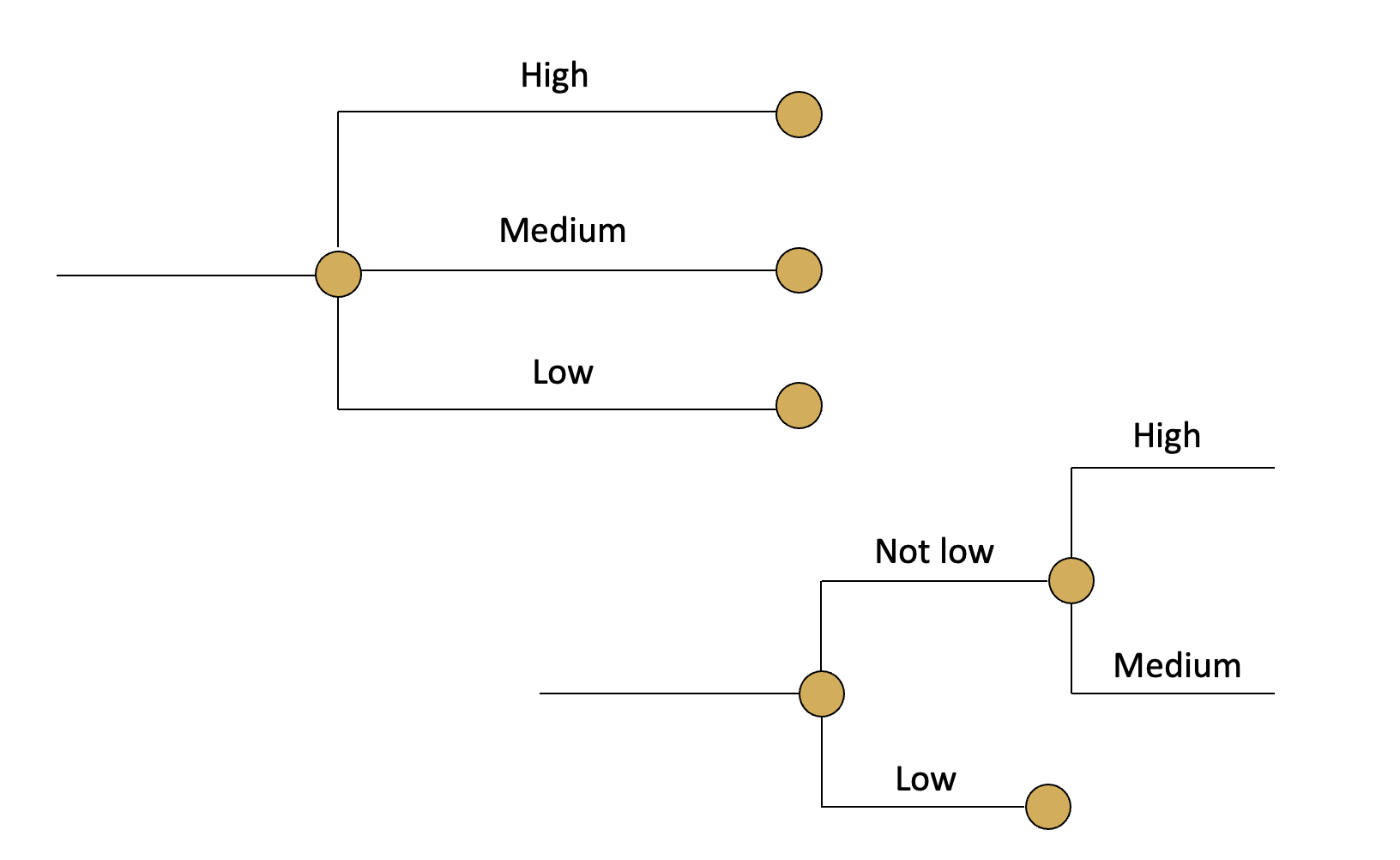

- Two branches versus three

There is nothing inherently wrong with having three (or more) branches, as long as events are mutually exclusive and probabilities sum to 1.

However, additional branches increase model complexity & can complicate sensitivity analyses without necessarily adding insight.

Some Do’s & “Dont’s”

- No embedded decisions

Each decision tree should address a single decision problem.

Embedding multiple decisions (e.g., screening and downstream treatment choices) complicates interpretation and validation.

Key Takeaways

Decision Trees

- Decision trees compare strategies by expected value

- Probabilities in trees are conditional by construction

- Good trees require mutually exclusive, exhaustive branches

Preview of what’s to come

More complex trees!

Questions?

Next: CEA Fundamentals 1: Costs