Introduction to economic evaluations

CEA Fundamentals: Valuing Costs

Learning Objectives and Outline

00

Learning Objectives

Identify theoretical and methodological differences between different economic evaluation techniques

Grasp the foundations of cost-effectiveness analysis

Describe the steps of valuing costs in economic evaluations & identify ways to curate cost parameters

Outline

01

02

CEAs: Identifying Alternatives

03

Valuing Costs

04

Data Collection

Introduction to Economic Evaluations

01

So far…

We’ve touched on the basic framework for decision analysis, focusing on:

Decision trees & probabilities

Bayes theorem & probability revision

Constructing decision trees using Amua

Now…

We will start to touch on some of the core concepts for representing costs and health benefits within decision problems.

Economic Evaluation

Relevant when decision alternatives have different costs and health consequences.

We want to measure the relative value of one strategy in comparison to others.

This can help us make resource allocation decisions in the face of constraints (e.g., budget).

Balancing $$ and Health Outcomes

Features of Economic Evaluation

- Systematic quantification of costs and consequences.

- Comparative analysis of alternative courses of action.

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/valuation of costs | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

Source: [@drummond2015a]

Cost analysis

Only looks at healthcare costs

Relevant when alternative options are equally effective (provide equal benefits). Rarely the case in reality!

Costs are valued in monetary terms (e.g., U.S. dollars)

Decision criterion: often to minimize cost

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Monetary units | Single effect of interest, common to both alternatives, but achieved to different degrees. | Natural units (e.g., life-years gained, disability days saved, points of blood pressure reduction, etc.) |

Source: [@drummond2015a]

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA)

Most useful when decision makers consider multiple options within a budget, and the relevant outcome is common across strategies

Costs

Costs are valued in monetary terms ($)

Benefits

Benefits are valued in terms of clinical outcomes (e.g., cases prevented, lives saved, years of life gained)

Results

Results reported as a cost-effectiveness ratio

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Example

Life Extension Example

Suppose we are interested in the prolongation of life after an intervention:

- Outcome of interest: life-years gained

- The outcome is common to alternative strategies; they differ only in the magnitude of life-years gained

- Results reported as: $/Life-years gained

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs both alternative | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Monetary units | Single effect of interest, common to both alternatives, but achieved to different degrees. | Natural units (e.g., life-years gained, disability days saved, points of blood pressure reduction, etc.) |

| Cost-utility analysis | Monetary units | Single or multiple effects, not necessarily common to both alternatives. | Healthy years (typically measured as quality-adjusted life-years) |

Source: [@drummond2015a]

Cost-Utility Analysis

- Essentially a variant of cost-effectiveness analysis.

- Major feature: use of summary measure of health: QALY.

- Quality-Adjusted Life Year (QALY): A metric that reflects both changes in life expectancy and quality of life (pain, function, or both).

- By far the most widely published form of economic evaluation.

Techniques for Economic Evaluation

| Type of study | Measurement/Valuation of costs both alternative | Identification of consequences | Measurement / valuation of consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost analysis | Monetary units | None | None |

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | Monetary units | Single effect of interest, common to both alternatives, but achieved to different degrees. | Natural units (e.g., life-years gained, disability days saved, points of blood pressure reduction, etc.) |

| Cost-utility analysis | Monetary units | Single or multiple effects, not necessarily common to both alternatives. | Healthy years (typically measured as quality-adjusted life-years) |

| Cost-benefit analysis | Monetary units | Single or multiple effects, not necessarily common to both alternatives | Monetary units |

Cost-Benefit Analysis

- Also known as Benefit-Cost Analysis

- Relevant for resource allocation between health care and other areas (e.g., education)

- Costs and health consequences are valued in monetary terms (e.g., U.S. dollars)

- Valuation of health consequences in monetary terms ($) is obtained by estimating individuals willingness to pay for life saving or health improving interventions. (e.g. US estimate of value per statistical life ~$9 million)

- Cost-benefit criterion: the benefits of a program > its costs

Notice that we’re not making comparisons across strategies–only comparisons of costs and benefits for the same strategy

To read more: Robinson et al, 2019

Cost-Benefit Analysis

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28183740/

Cost-Benefit Analysis

https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/S2194588818000271/type/journal_article

Back to Cost-Effectiveness Analysis!

Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Formula

The CEA Formula

Relevant when healthcare alternatives have different costs & health consequences

\frac{\text{Cost (Intervention A) - Cost (Intervention B)}}{\text{Benefit (A) - Benefit (B)}}

Relative VALUE of an intervention in comparison to its alternative is expressed as a cost-effectiveness RATIO

Who uses economic evaluations?

Health Technology Advisory Committees

NICE (The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, UK)

Canada’s Drug and Health Technology Agency

PBAC (Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee in Australia)

Brazil’s health technology assessment institute

Groups developing clinical guidelines

WHO

CDC

Disease-specific organizations: American Cancer Society; American Heart Association; European Stroke Organisation

Regulatory agencies

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration)

EPA (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency)

CEAs: Identifying Alternatives

02

Identifying Alternatives

Decision modeling / economic evaluation requires identifying strategies or alternative courses of action.

Alternatives Include:

Different therapies

Different policies

Different technologies

Different combinations

Different sequences of events

Different treatment ages

Once we have identified the alternatives, we’ll want to quantify their associated consequences in terms of:

- Health outcomes

- Costs

CEA components

\frac{\text{Cost (Intervention A) - Cost (Intervention B)}}{\text{Benefit (A) - Benefit (B)}}

Valuing Costs

03

Valuing Costs: Steps

1

Identify

Estimate the different categories of resources likely to be required

(e.g., surgical staff, medical equipment, surgical complications, re-admissions)

2

Measure

Estimate how much of each resource category is required

(e.g. type of staff performing the surgery and time involved, post-surgery length of stay, re-admission rates)

3

Value

Apply unit costs to each resource category

(e.g., salary scales from the relevant hospital or national wage rates for staff inputs, cost per inpatient day for the post-surgery hospital stay)

Source: Gold 1996, Drummond 2015, Gray 2012)

We can identify different types of healthcare costs

Direct Health Care Costs

- Hospital, office, home, facilities

- Medications, procedures, tests, professional fees

Direct Non-Health Care Costs

- Childcare, transportation costs

Time Costs

- Patient time receiving care, opportunity cost of time

Productivity Costs

- Impaired ability to work due to morbidity

- Lost economic productivity due to death

Unrelated Healthcare Costs

- Cumulative trajectory of total healthcare costs over time (unrelated to medical interventions)

Identifying Costs in Practice

- Count what is likely to matter

- Exclude what is likely to have little effect or equal effects across alternatives

- Any exclusion must be noted & possible bias examined

- We are constrained by what data are available

We can measure costs using different approaches

Micro-costing

(bottom-up)

- Measure all resources used by individual patients, then assign the unit cost for each type of resource consumed to calculate the total cost

Gross-costing

(top-down)

- Estimate cost for a given volume of patients by dividing the total cost by the volume of service use

- Example: Downstream costs (e.g., hospitalization due to opioid overdose)

Ingredients-based approach

(P x Q x C)

- Probability of occurrence (P)

- Quantity (Q)

- Unit costs (C)

Whose perspective?

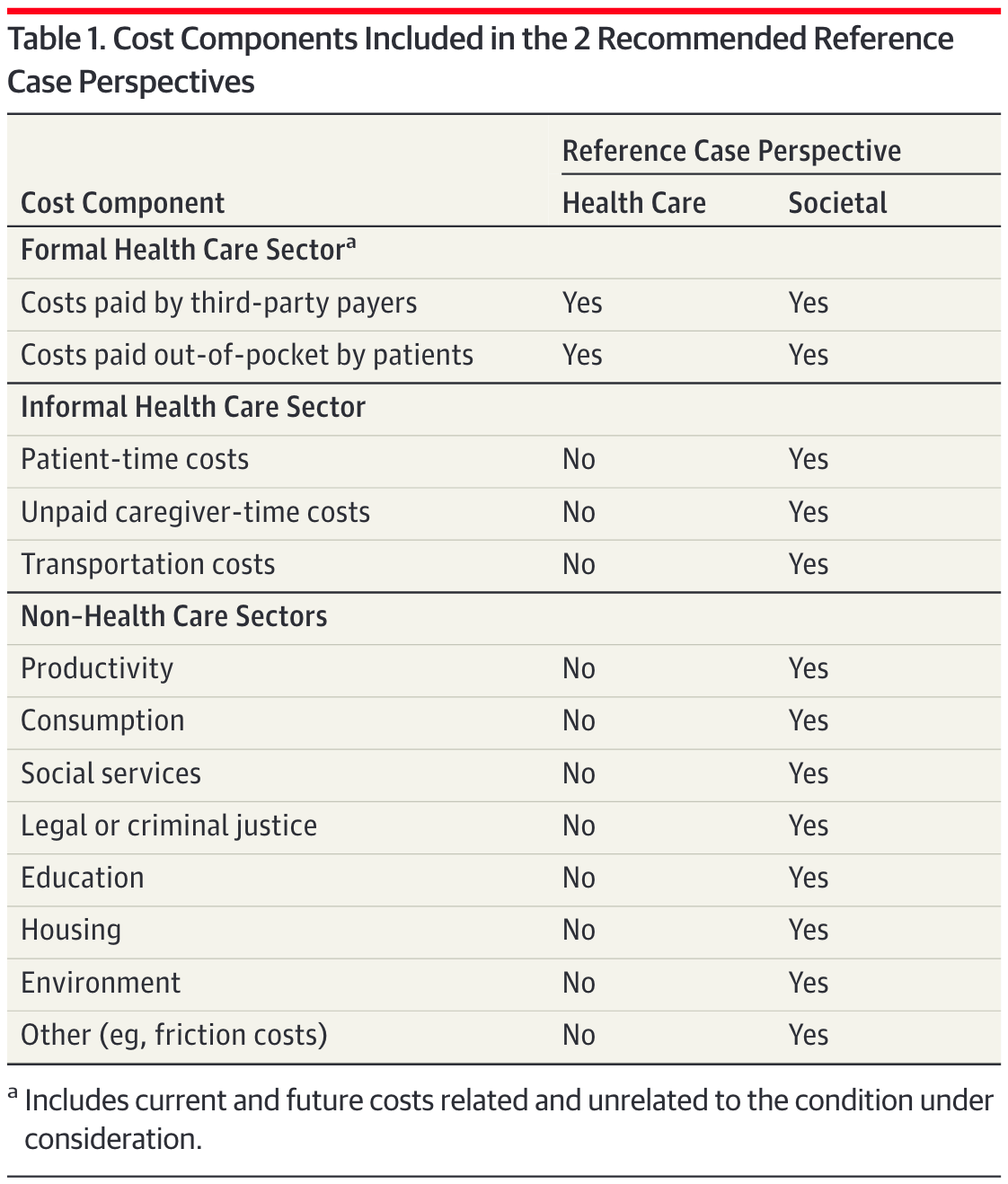

Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses: Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. 2016;316:1093–1103.

Whose perspective?

PERSPECTIVE MATTERS

Formal Healthcare Sector: Medical costs borne by third-partypayers & paid for out-of-pocket by patients. Should include current + future costs, related & unrelated to the condition under consideration

Societal perspective: Represents the wider “public interest” & inter-sectoral distribution of resources that are important to consider - reflects costs on all affected parties

Perspective Example: Mammography

Formal Healthcare Sector:

- Costs associated with the screening itself [mammogram procedure + physician time]

- Costs of follow-up tests for both false-positive & true positive results

- Downstream costs (or savings) associated with cases of breast cancer, such as: Hospitalization + treatment costs

- Costs unrelated to medical intervention/disease; of living longer due to mammography

Societal perspective:

- Costs associated with the screening itself [mammogram procedure + physician time]

- Costs of follow-up tests for both false-positive & true positive results

- Downstream costs (or savings) associated with cases of breast cancer, such as: Hospitalization + treatment costs

- Costs unrelated to medical intervention/disease; of living longer due to mammography

- Patient productivity losses associated with the screening or cancer treatment

- Childcare/transportation costs

Data Collection

04

Two Approaches for Data Collection

Approach 1

Alongside clinical trials

Collect cost data directly during the trial

Approach 2

Using secondary data

Leverage existing databases, registries, and published literature

International versus US will have different approaches

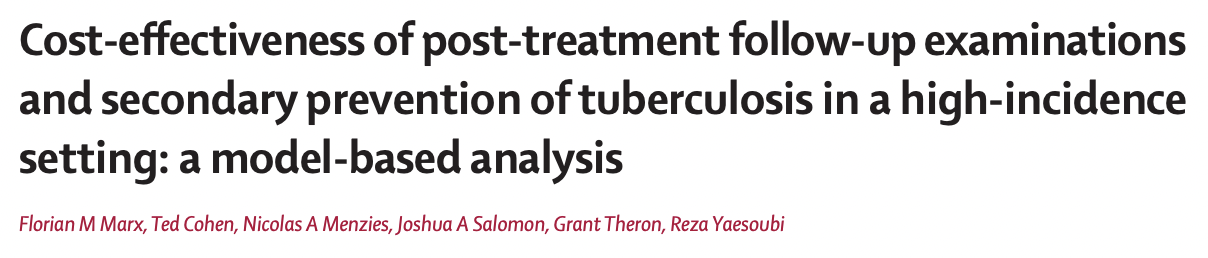

Costs (International)

1

Local Data

In-country registries, hospital data, donor databases

2

Literature

Published cost studies

3

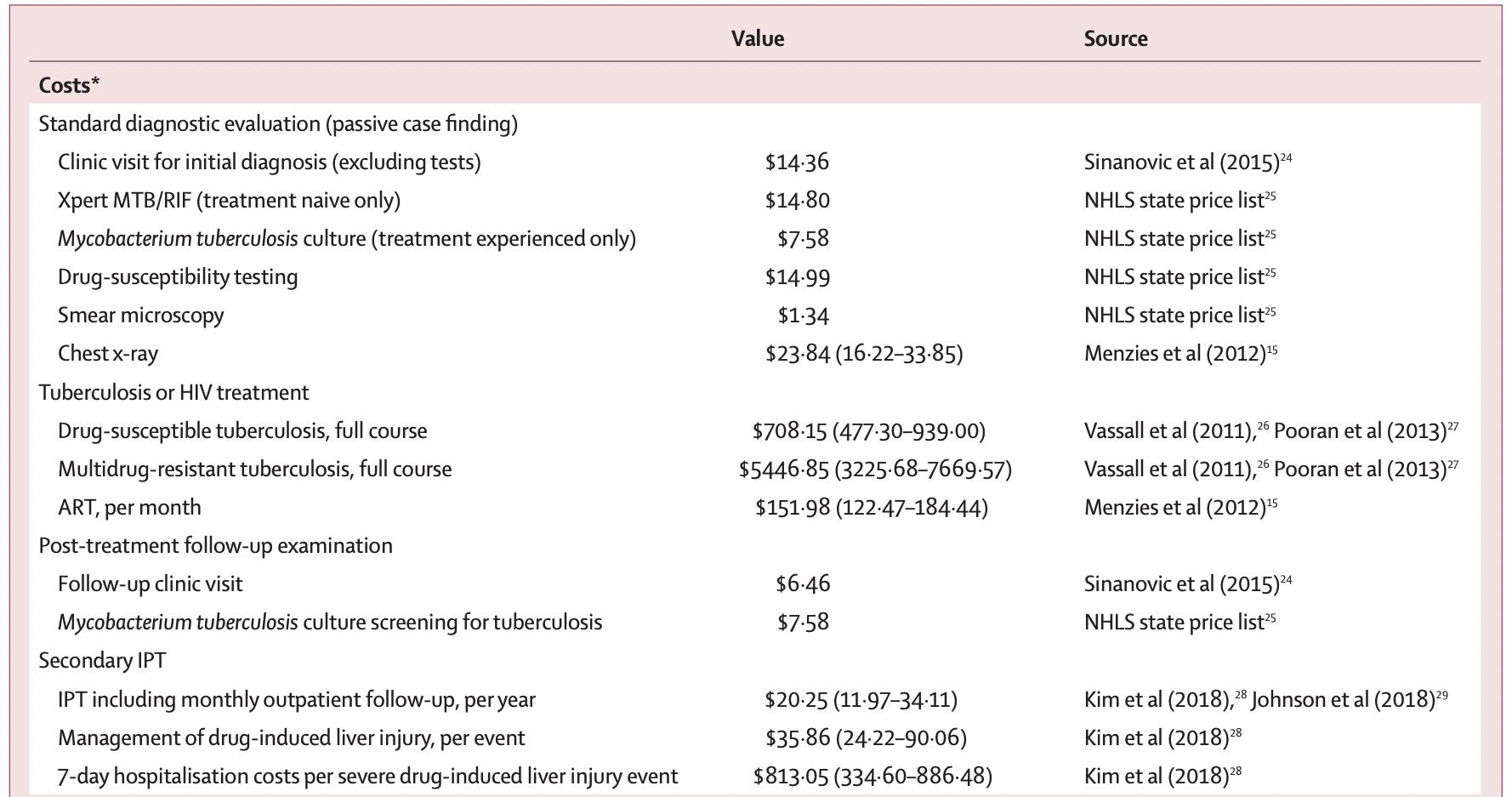

Tufts CEA Registry

Comprehensive database

4

DCP3

Disease Control Priorities

The key is to get as close to the “true” cost associated with each procedure per patient

E.g., “TB healthcare & diagnostics are from official price list of the National Health Laboratory Service in South Africa; Costs for follow-up reflect local clinic and culture-based screening for active-tuberculosis”

Costs (Published Literature)

Costs (Published Literature)

Costs (Tufts CEVR)

https://cevr.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/databases/cea-registry

Costs (Tufts CEVR)

Costs (Tufts CEVR)

Costs (Tufts CEVR)

http://ghcearegistry.org/ghcearegistry/

Costs (Tufts CEVR)

Costs (DCP3)

Adjustments needed for Valuing Costs

01

Inflation adjustment

02

Adjusting for currency and currency year

03

Discounting

Inflation Adjustment

Inflation Adjustment: Motivation

The Problem

$100 in 2000 is not equivalent to $100 in 2020

$100 could buy a lot more in 2000!

The Solution

Important to adjust for the price difference over time, especially when working with cost sources from multiple years

Inflation Adjustment: Example

Inflation Adjustment: Method

1

Choose Reference Year

Usually the current year of analysis

2

Convert All Costs

Convert to reference year

3

Apply Formula

Use price index ratio

Converting cost in Year X to Year Y (reference year):

\textbf{Cost(Year Y)} = \textbf{Cost(Year X)} \times \frac{\textbf{Price index(Year Y)}}{\textbf{Price index(Year X)}}

Inflation Adjustment: Example

Example Problem

Cost of hospitalization for mild stroke in the US was ~$15,000 USD in 2016. Convert to 2020 USD.

Solution:

- PCE (Personal Consumption Expenditure Health Price Index) in 2016: 105.430

- PCE in 2020: 112.978

\textbf{Cost(2020)} = 15,000 \times \frac{112.978}{105.430} = \$16,674 \text{ (2020 USD)}

Currency Conversion

Currency Conversion Basics

When Needed

Not required for CEA but may be useful:

- Convert local currency to USD for international comparisons

- Cost-effectiveness thresholds often estimated in USD per DALY

How to Convert

Example: 1,000 Philippine Peso to USD

- Current exchange rate (2026): 1 Philippine Peso = ~0.017 USD

- Result: 1,000 Peso = $16.87 USD

Discounting

Why Discounting?

Purpose

Adjust costs at social discount rate to reflect social “rate of time preference”

Reasons

- Pure time preference (“impatient”)

- Potential catastrophic risk in the future

- Economic growth/return on investment

Discounting

A $ today is NOT worth a $ tomorrow

$100 now

2% net return

$102 next year

The “present value” of $102 next year is $100 today.

Similarly, $100 next year = $98.04 today

Inflation vs. Discounting

Inflation Adjustment

We convert PAST costs to present-day values

Discounting

We convert FUTURE costs to present-day values

Present Value Formula

PV = \frac{FV}{(1+r)^t}

Where:

FV = future value, the nominal cost incurred in the future

r = annual discount rate (analogous to interest rate)

t = number of years in future when cost is incurred

Standard rate: Reasonable consensus around 3% per year (may vary by country guidelines)

Important! Adjust for inflation and currency first, then discount

Intuition

r = 0.03

PV = FV/(1+r)^t, and we’re at Year 0:

| Year | Formula | Value of $1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | $1/1.03^0 | $1 |

| 1 | $1/1.03^1 | $0.97 |

| 2 | $1/1.03^2 | $0.94 |

| 3 | $1/1.03^3 | $0.92 |

What would $1 be in Year 2 be in the PRESENT VALUE of today?

Today, it will be 0.94.

Discounting Example

Example Problem

Assume in year 5, a patient develops disease, and there is a treatment cost of $500. What is the present value?

Solution:

PV = \frac{FV}{(1+r)^t} = \frac{500}{(1+0.03)^5} = \$431.30

Key Takeaways

Costs

- Different types of economic evaluation

- CEA uses cost-effectiveness ratios

- Perspective matters for cost inclusion

- Adjust for inflation & discount future costs

Questions?

Next Lecture: Benefits & QALYs