Probability review

Rates & Probabilities

Learning Objectives and Outline

00

Learning Objectives

Differentiate between rates and probabilities conceptually

Interpret rates and probabilities in applied examples

Identify and correctly interpret rates and probabilities in the literature

Outline

01

02

Rates review

03

Rates versus probabilities

04

Summary

05

Identifying rates and probabilities in the literature

06

Translating between rates and probabilities

Probability Review

01

Probability

Probability is the likelihood that an event occurs within a specified time period.

Out of everyone we followed for this period, what fraction experienced the event?

Probability can be reported in different ways

Proportion / percentage: 0.40 or 40%

Frequency: 40 per 100 (or 4 per 1,000)

Odds: P/(1-P) (ranges from 0 to \infty)

Epidemiologic terminology: - Cumulative incidence (risk): the probability of experiencing the event by time t - Examples: “1-year risk,” “5-year cumulative incidence”

Rates

02

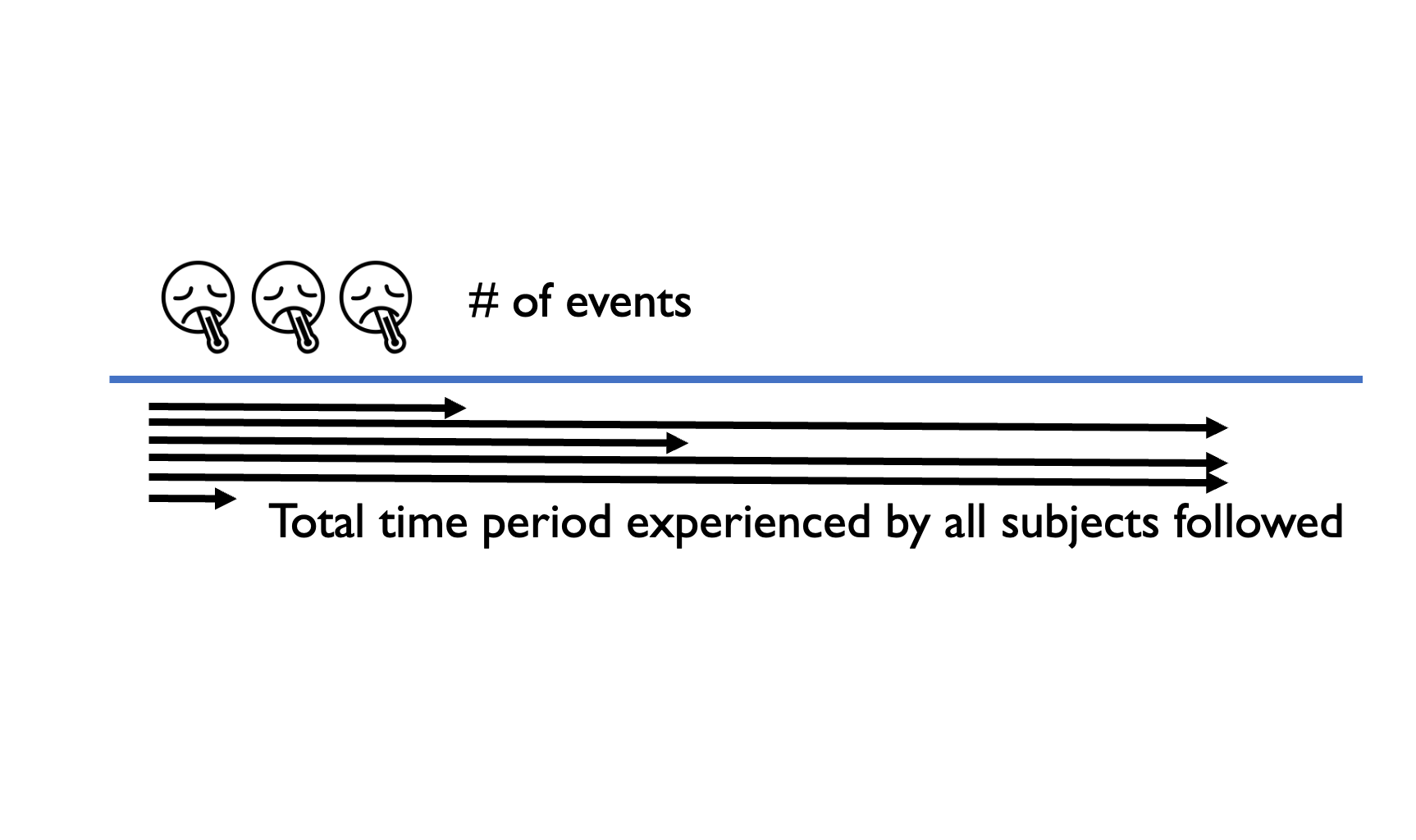

Rates involve person-time

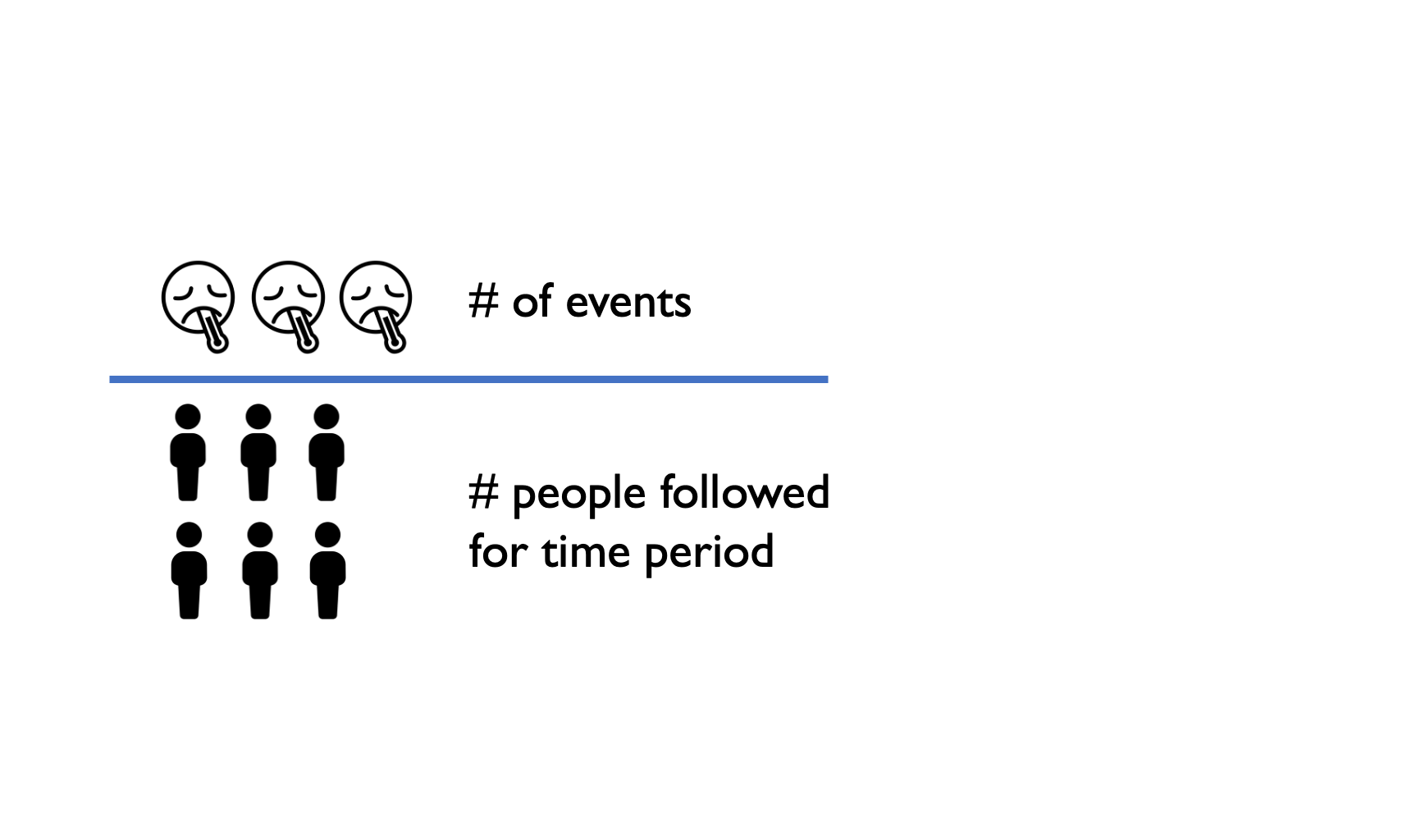

Incidence (hazard) rate: number of events per unit of person-time

Rates describe how fast events occur

Rates can range from 0 to \infinity

What is the difference between a rate and a probability?

Rates vs. probabilities

03

Rates vs. probabilities

Probability (risk): chance an individual experiences an event by a specified time

Rate: speed at which events occur per unit of person-time

Key distinction: rates use person-time in the denominator; probabilities do not

- **Probabilities collapse into a time window (10% by year 1; 30% by 3 years; it’s cumulative);

- **Rates have time in the denominator

Rate (incidence rate)

Probability (risk)

Example: same study, probability vs. rate

Study: 100 people followed for up to 4 years; 40 deaths.

Probability (risk) over 4 years: 40/100 = 0.40 ;

Interpretation: 40% died within 4 years.

Rate (if all 100 followed for 4 years): Total person-time = 100 \times 4 = 400 person-years; 40/400 = 0.10 deaths per person-year

Interpretation: 0.10 deaths occur for every 1 person-year of follow-up; or around 1 death per 10 person-years of follow-up across the study population

Timing & censoring

- Rates change when follow-up time differs, even if the number of events is the same

- Censoring or dropout reduces person-time and can increase the estimated rate

Example: events happen early vs. late

Study: 100 people, planned follow-up = 4 years

Case: 40 deaths occur in Year 1

- Person-time = (40 \times 1) + (60 \times 4) = 280 person-years

- Rate: 40/280 = 0.143 deaths per person-year

- Probability (risk): 40/100 = 0.40

When time-at-risk is not reported1

- When individual follow-up time is unavailable, events are often assumed to be evenly distributed

- This approximates equal person-time for everyone

- If events occurred earlier, the true rate would be higher (and vice versa)

Summary: Rates vs. Probabilities

04

Summary: Rates vs. Probabilities

- Probability

- Answers: What proportion of people experience the event by time X?

- Rate

- Answers: How fast do events occur, per unit of time at risk?

Summary: Rates vs. Probabilities

| Measure | Formula | Range | Used in |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | \dfrac{\# \text{events}}{\text{total person-time}} | 0–\infty | Rate matrices |

| Probability / risk | \dfrac{\# \text{events}}{\# \text{people followed}} | 0–1 | Probability matrices |

Identifying rates/probabilities through the literature

05

Identifying rates/probabilities through the literature

Identifying rates/probabilities through the literature

Translating between rates and probabilities

06

Converting rates/probabilities

- Rates are instantaneous; they represent the speed of an event happening & because speed scales linearly with time, you can multiply or divide rates when the time period changes.

- Probabilities are accumulated outcomes (they are cumulative & bounded between 0-1); they do not scale linearly with time. You can’t have more than 100% risk; so dividing/multiplying them does not preserve the correct relationship over time.

Another way of saying the same thing:

- A rate tells us how fast an event occurs; it scales with time.

- A probability tells us whether an event occurs within time “t”; it is cumulative & bounded. The relationship with time is non-linear because the chance of an event slows as fewer people remain at risk (i.e., why we say it’s “cumulative”)

Conversions

- A standard Markov model assumes an exponential (constant-hazard) process.

- This allows conversion between rates (instantaneous) and probabilities (over time).

- If the hazard changes over time, simple conversions no longer apply.

Rate to Probability p = 1 - e^{-rt}

Conversions

Probability to Rate

r = \frac{-ln(1-p)} {t}

Conversions

- exp(x): Applies continuous time accumulation (when converting rates to probabilities; the exponential ensures probabilities stay between 0 & 1 and that the timing of events is modeled correctly)

- ln(x): Removes it (when converting probability to rate)

Conversions

Example: Consider we have a 12-month probability of 10.8% that a child under age 6 is newly diagnosed with elevated blood lead levels. If your Markov model has a 3-month cycle length, a 3-month probability is needed.

Conversions

STEP 1 Convert the 12-month probability to a 12-month rate (or 12-month probability to a 3-month rate)

Note

Cannot divide/multiply probabilities

r = \frac{-ln(1-p)} {t}

r = \frac{-ln(1-.108)} {1} = 0.1142891

Note

Since the time period doesn’t change, the denominator is 1

Conversions

STEP 2 Convert the 12-month rate to a 3-month rate

\frac{0.1142891}{4} = 0.02857228

Conversions

STEP 2 Convert 3-month rate to 3-month probability

p = 1 - e^{-r\Delta t}

p = 1 - e^{−0.02857228∗1} = 0.028168

Conversions

OR, Step 1 Convert the 12-month probability to a 3-month rate

r = \frac{-ln(1-p)} {t}

r = \frac{-ln(1-.108)} {4} = 0.02857229

Conversions

STEP 2 Convert 3-month rate to a 3-month probability

p = 1 - e^{-r\Delta t}

p = 1 - e^{−0.02857229∗1} = 0.028168

Conversions

Note

***IF we took the probability of .108 / 4 to get the 3M probability, we would get 0.027. This is CLOSE but it could make a huge difference when modeling hundredths of thousands of individuals, for example

Alternative Rate-to-Probability Conversions

- Long cycles can include multiple transitions (healthy → sick → dead).

- Standard rate–probability conversion

p_{HS}= 1 - e^{-r_{HS}\Delta t}

treats transitions independently, ignoring competing risks. - This hides within-cycle events.

- Can underestimate deaths with long cycles.

- Fix: shorter cycles or competing-risk conversions.

Alternative Rate-to-Probability Conversions

A set of formulas often used to account for competing risks are as follows:

p_{HS}= \frac{r_{HS}}{r_{HS}+r_{HD}}\big ( 1 - e^{-(r_{HS}+r_{HD})\Delta t}\big )

p_{HD}= \frac{r_{HD}}{r_{HS}+r_{HD}}\big ( 1 - e^{-(r_{HS}+r_{HD})\Delta t}\big )

p_{HH} = e^{-(r_{HS}+r_{HD})\Delta t}

What to use

| Equation | Use case | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| p = 1 - e^{-rt} | When you know a rate but need a probability for a fixed cycle length | Simple closed-form conversion under a constant (exponential) hazard |

| r = -\ln(1-p)/t | When you have a probability but need a rate to rescale across time intervals | Preserves the correct exponential relationship when changing cycle length |

| Competing-risk formulas p_{HS}, p_{HD} | When more than one event can occur from the same state (e.g., Healthy → Sick and Healthy → Dead) | Properly accounts for competing hazards and prevents hidden within-cycle events |

Alternative Rate-to-Probability Conversions

There’s an even more accurate way to correct for “competing risks” & while it’s beyond the scope of this introductory workshop, we will briefly review how to do this within the Markov lecture.

Key Takeaways

Rates & Probabilities

- Probabilities are cumulative and bounded (0-1)

- Rates are instantaneous and scale with time

- Conversions require a constant hazard assumption (hazard is flat within a time interval)